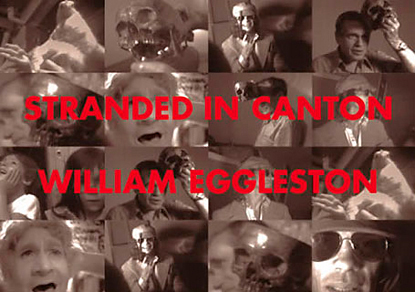

"Flyer for 'Stranded in Canton,' " All rights reserved

In 2006 I attended the premier screening of legendary photographer William Eggleston’s only film, a documentary titled “Stranded in Canton,” at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater. Shot from 1973-75, the film had been recently edited by Eggleston and co-director Robert Gordon, who were at the screening in person. This is the review I wrote for the Society’s magazine, which has since gone offline. Tim Connor, 2012

William Eggleston’s documentary, “Stranded in Canton,” breaks through boundaries as disdainfully as Eggleston’s then-shocking color pictures blurred art and documentary and led the way for photography to appear on museum walls in the 1980s. From 1973 to 1975 Eggleston videotaped more than 30 hours of footage with an early Sony Porta Pack, fitted with a “prime” Zeiss lens and, occasionally, with an infrared tube that allowed shooting in near darkness. Thirty-three years later the film made out of that footage carries a gut-punching intensity.

In the film Eggleston’s dry voiceover explains that he “…shot everything, wherever I happened to be…” but his subjects -- mostly friends at bars and private parties in Memphis, New Orleans and Mississippi—are no ordinary bunch.

It was the early 70s (popularly known as the 60s) and excess was in fashion. Drugs still had a prophetic sheen and people wanted to believe, with Jim Morrison, they could “break on through to the other side.” Loaded on booze and pharmaceuticals, Eggleston’s friends in the movie vie with each other – to roar and chant tall tales, songs and tirades into the Southern night. Often they succeed in invoking a truly extreme quaalude voodoo delta strangeness.

Their filmic intensity owes a lot to Eggleston’s unblinking no-judgment choices. His unfussy way of moving the camera in exact sync with his curiosity, and of holding his subject in long, still super- tight close-ups seems to have spurred his characters on to performance extremes. The uninterrupted close-ups and winding tracking shots sometimes even make the viewer uncomfortable. There’s more than technique at play here.

No matter how woozy the action gets – and it includes biting the heads off live chickens and a casual game of Russian roulette – Eggleston’s camera stays cool, despite the intensity of the performances and the intimacy created by all those super tight close-ups.

At the time the Sony only shot in black and white. It’s interesting that with his trademark color gone Eggleston’s film relies heavily on sound. And, true to the period, the music – glorious, soulful blues, mostly by renowned Memphis bluesman, Furry Lewis– is the best thing in a very good film.

But the post-screening question-and-answer session was disappointing. Dressed in a light-colored suit, bow tie and skin-tight black leather gloves, Eggleston, along with his co- director Gordon, fielded queries that were almost uniformly technical. One cinephile called the film a “gorgeous object” and then asked: “how was the sound quality achieved?” Audience members wanted to know how using the Porta Pack compared to Eggleston’s still camera, how the tape was transferred to digital, what was the editing procedure? There was nothing wrong with these questions, but I was absorbed in contemplating the end credits, which detailed what had happened to Eggleston’s friends, in the three decades since they appeared in the film.

Two had been murdered, one shot to death by a pharmacist the victim had tried to hold up for barbiturates. A couple seen bickering in the film had both committed suicide. One of the musicians had disappeared. Another, like Eggleston an apparent survivor, was “a recording artist in Mississippi.” Two other characters had died young, causes unstated - perhaps a reasonable guess would be booze and/or AIDS. And the beautiful woman who had been Eggleston’s girlfriend, she of melting close-ups in the film, was summed up this way: “owns rental properties.”

I was too shy too ask Eggleston my question: “Do you believe in ghosts?”

1 comment:

Tim - this piece of genius takes all my words away - except 'Do you believe in ghosts?' Ya shudda askt it.

Post a Comment