Austrian photographer Heidrich Kuehn

was a friend of well-known American shooters Alfred Stieglitz and Edward

Steichen around the turn of the last century. The three men visited each other and

took pictures together in both the U.S. and Europe; Stieglitz and Kuehns also corresponded

vociferously for over 30 years.

This trans-Atlantic artistic friendship

is the basis of a new show, “Heidrich Kuehn and His American Circle: Stieglitz

and Steichen,” at the Neue Galerie.

No doubt the concept serves as an excuse to pull in American audiences

who know Stieglitz and Steichen, but it’s also a fascinating exercise in

curatorial sleuthing. As the show makes

clear, ideas did flow freely among the men. We can literally see Kuehn’s bold romantic

use of natural symbols like trees and clouds turn up in prints by Stieglitz and

Steichen. At the same time the Modernist tendencies of the two New Yorkers start

to appear in Kuehn’s painterly landscapes.

But what impresses most about this show is the sheer

impact of its century-old prints.

In a back room the show’s curator

Monika Faber has reconstructed an installation of Kuehn’s large-sized

Pictorialist land- and seascapes that appeared in 1906 in Stieglitz’s Gallery

291. The approach is as insistent as any contemporary artist aiming to grab

eyeballs. Strongly tinted in cyans, greens, brick reds and carroty oranges, the

pictures seem to leap out of their frames. Hardly the faded stuff of ancient

photo history, they are brassy and

bright as a new penny.

Later, Kuehn’s Stieglitz-inspired

turn toward Modernist clarity also exhibits a freshness one rarely sees in

large-format pictures before 1920. Abandoning the large prints, universal

themes and impressionist effects of Pictorialism, Kuehn launched into Modernism

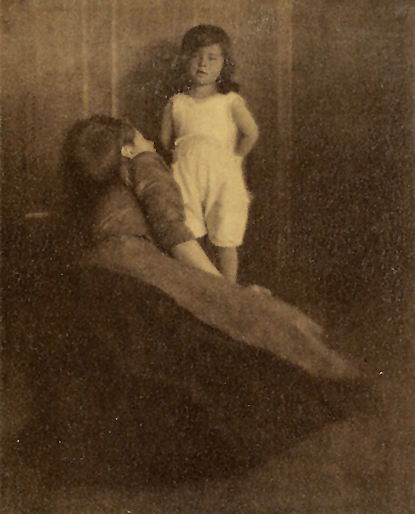

by making intimate, psychologically–telling portraits of his family.

A recent piece by Karen Rosenberg

in the New York Times calls Kuehn

“one of the medium’s great control freaks” and describes how, in making the

family portraits, “…he selected a site and sketched it in pencil, had his

children and their nanny assume specific poses in clothing he had preselected

for its photogenic qualities, and waited until every shadow was right where he

wanted it to be.”

Yet Kuehn’s portraits in this

show – even those in color, using the then-new Autochrome process -- seem

remarkably unposed, warm and natural.

How could such a punctilious taskmaster produce such relaxed work? The answer probably lies with the

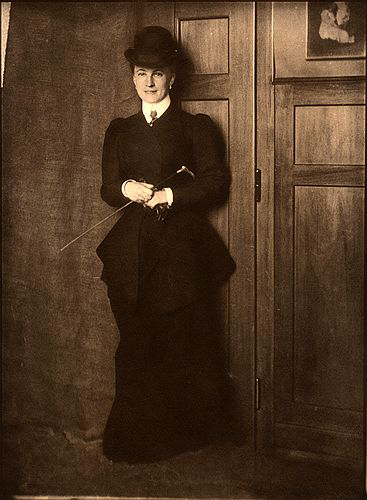

family’s young English nanny, Mary Warner, who had taken charge of Kuehn’s four

children after his wife died. Photographed by Kuehn with his children, Warner

seems a tender presence. When she reveals her face to the lens she is nothing

short of radiant.

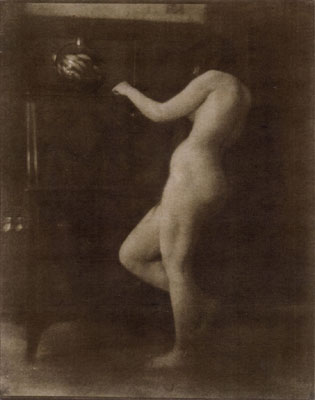

It comes as no surprise that,

during this period, master and nanny were lovers. Later, as Kuehn’s companion,

Warner posed for an erotically charged series of nudes, some of which are

included in the show.

After that, Kuehn’s story goes

swiftly down hill. The First World War devastated his traditional world. He lost his money and stopped reaching

out to the great world beyond his Tyrolean hills. In the end – so the story

goes – Kuehn became a crank and finally a recluse.

I wonder what happened to Mary

Warner?

No comments:

Post a Comment