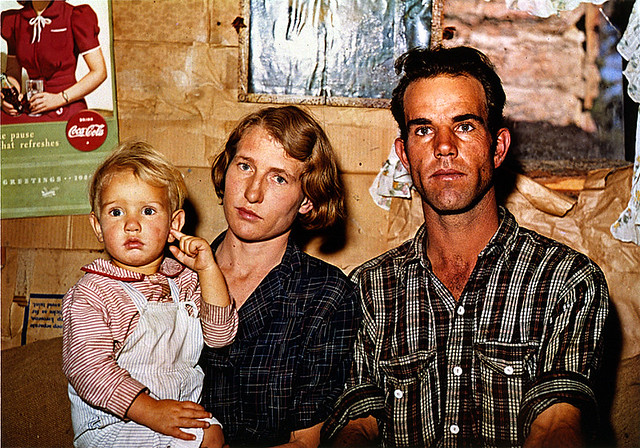

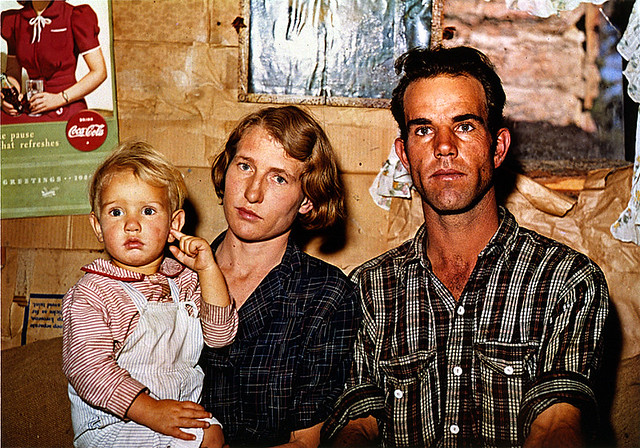

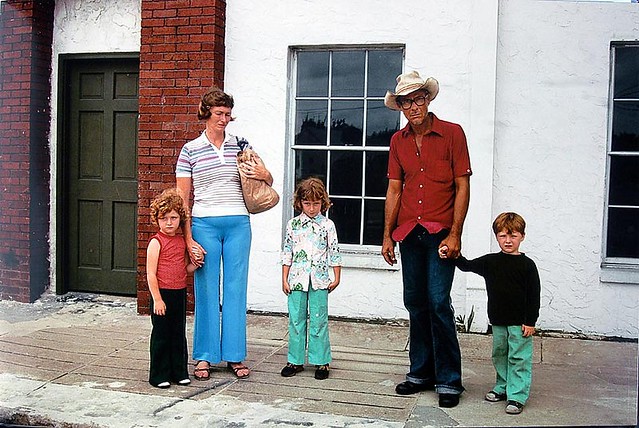

Russell Lee, Jack Whinery, Homesteader and Family, Pietown, New Mexico, September, 1940

Russell Lee, Jack Whinery, Homesteader and Family, Pietown, New Mexico, September, 1940

The 31 photographers included in "Everyday America, Photographs from the Berman Collection," at Kasher Gallery cover more than 75 years of

America’s story, but the people

and events scholars might deem the proper content of our national history are

not here. Instead the photographers present a sort of hodgepodge history of

images anyone might have noticed -- and possibly thought unremarkable. Here’s

a partial list of subjects: houses, shopkeepers, vehicles, lovers, amusement parks,

suburbs, couples, orchards, graves, dancers, motels, kids, train trestles, shoppers,

barber shops (I could go on and on).

This is a different kind of history, and I

don’t mean to make fun of it. On the contrary, arranging the pictures outside a

historical context seems in keeping with their essential idea – they were shot in history, not about it. By not

attaching the photographers’ names and picture titles alongside the works, the curators

go further toward isolating the images in their own discrete moments (catalogs are readily available). I found

the disorientaion refreshing. The experience became just me and the images – like peering

though a viewfinder moving randomly through time.

And the pictures are superb. Roughly grouped under the rubric of

“documentary,” the photographers avoid sentimentality and (except for one

mocking photo by Martin Parr) post-modern irony. Their tool of choice is most

often a large, unwieldly 4x5 or 8x10 view camera, which requires fixed

intentions and emphasizes clarity and specificity.

Arguably, almost all the styles in this show can

be understood as versions of Walker Evans’ style. And, indeed, Evans -- with

the largest number and often the best pictures in the show -- is the star here.

We see, for example, his fascination with the art and language of commercial

displays – he called them “the pitch direct” –echoed in pictures by Aaron

Siskind and John Vachon and expanded to church signs and scribbled graffiti by

Dorothea Lange and Helen Levitt.

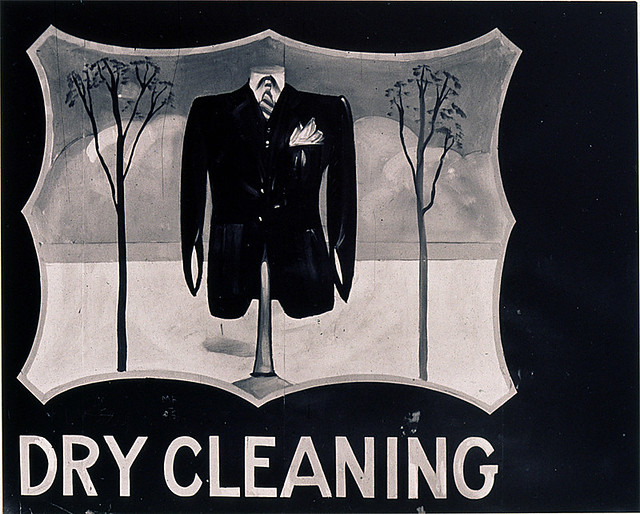

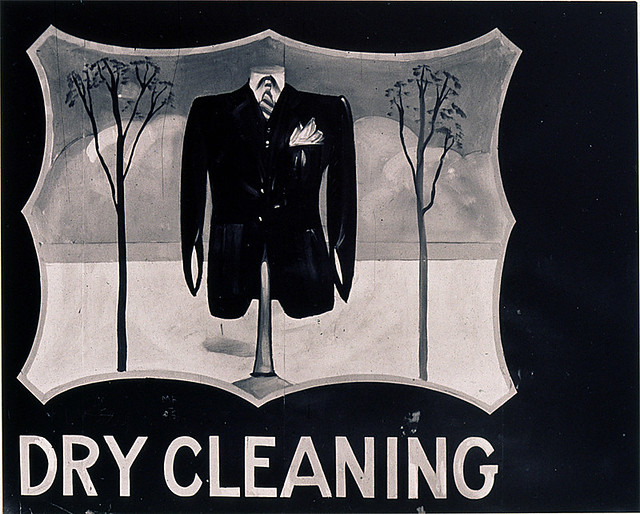

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935”

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935”

Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

It was Evans who first understood that the

written word in public is important socially and aesthetically. His homage to skilled and graceful

sign-painting in “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1935” and minimalist white-paint-on-black board in “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936,” for instance, show us that – long before MBAs discovered them

-- brands were, for good or evil, indelible.

Or they can be chaotic, as Robert Frank shows in

his 35mm. New York street shot, “Untitled (Poultry Store Front), 1950s. ” In

the shot a messy script, daubed on a sign above a trash-filled sidewalk, maniacally

proclaims “1-pound giblets for $3” over and over and over. This is Frank working characteristically

against the grain. He is no doubt well aware that the signs’ thumbed-nose to

craftsmanship represents a social change. What has happened to Evans’ folk artist/sign painter? Is he drunk? Or has be been replaced by a

machine?

The transformation of the show’s themes over

time is one of its great pleasures. For instance, John Humble, a west coast photographer

has photographed the streets and buildings of Los Angeles in large-format color

since the 1970s. His color shot of a low-slung fast-food restaurant, the show’s

“12511

Venice Blvd, Mar Vista (Canton Kitchen), 1997” at first seems garish with multiple signs and neon windows. But we soon understand that Humble’s picture is in its way as modest

and precise as one of Evans.

John Humble, 12511 Venice Blvd., Mar Vista (Canton Kitchen), January 8, 1997

What’s different in this picture (aside from

the color) is the rest of the world. The Canton Kitchen itself, a place about

the size of a Manhattan studio apartment, is crouched in the shadow of an

appliance parts warehouse under an illuminated billboard and, on the other side,

pushed up against a nondescript parking lot. Given this, and the fact that no

one walks in L.A., it’s hardly surprising that four signs are needed -- one of

them towering above the tiny building (Chinese FOOD to GO). We’re not in 1930s Connecticut

anymore.

Numerous examples from the show make clear that

Evans was drawn to deserted, closed and boarded-up buildings, a theme repeated here

by William Christenberry, Jack Delano, David Husom and Mitch Epstein, among

others. But where Christenberry’s freshly-painted white church, in Hale County,

Alabama in the 1970s, for example, exudes hope despite the boards nailed over

its windows, Epstein’s bricked-up factories in Holyoke, Massachusetts in 2000

emanate despair. Buildings have a spirit, just like living creatures.

It was Evans’ great gift to infuse inanimate

objects with a tender life most photographers grant only to other human beings.

But, perhaps as a corollary of this, he seemed reluctant throughout his career

to make intimate portraits, preferring to pose people in the midst of larger

scenes, if at all. (An exception – perhaps a telling one – is his New York City series of subway portraits, shot in secret, spy-camera-style.)

Mitch Epstein, Newton Street Row Houses, (Brownstone Building), Holyoke, Massachusetts, 2000

Mitch Epstein, Newton Street Row Houses, (Brownstone Building), Holyoke, Massachusetts, 2000

Could an unconscious aping of Evans’

people-shyness by curators or collector explain why so few portraits are in

this show? It’s a real surprise, given the size of the space, that all the significant

people pictures can be grouped in one corner. Clearly, this is not because they’re unconvincing or weak.

On the contrary, this section of the show may be its liveliest.

This is in spite of the fact that many of the

portraits in “Everyday America” are not “everyday” at all. They are classic

black and white prints by Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White and other

Depression-era shooters of refugee families and young working men fleeing the

dust-bowl. These dramatic pictures

are interesting, but there’s something musty and old-fashioned about them. They were widely published at the time and are now so well-known as a genre it’s

hard to really see them clearly. But then comes an early color shot by FSA

photographer Russell Lee to pierce through the decades.

In Lee’s picture, “Jack Whinery, Homesteader

and Family, Pietown, New Mexico, September, 1940,” (see it top of this review) a handsome young working-class man and his

blonde, blue-eyed wife, holding their toddler son, stare resolutely into the

camera. Behind them is the

cardboard-covered wall of their new rough-built shack with plastic stretched

over an unframed window. A swatch of flowered fabric for curtains is

tentatively pinned up near the window. A Coca-cola poster is hanging on the

wall.

To me this picture says, “We are a God-fearing, can-do American family, and we are not afraid.” My question might be, Why not? The Great Depression is still hanging on, and another great war is looming in Europe. Yet, as

a viewer, I believe in this family. Here in America they’ll make it, I'm sure.

In the final reel, I tell ourselves, everything will work out.

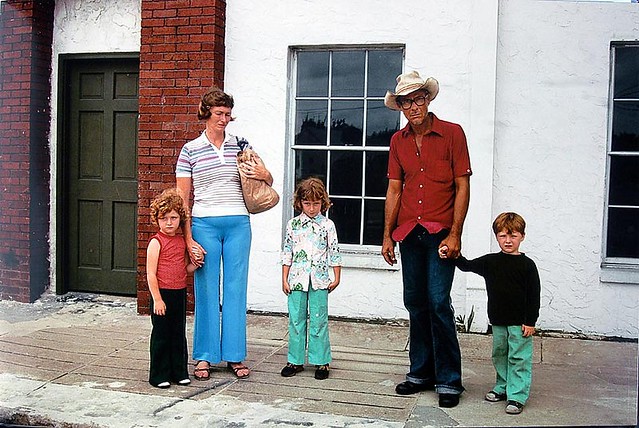

Mitch Epstein,

Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983

By 1983, when Mitch Epstein made “Ybor City,

Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), ” belief is harder to come by. In Epstein’s

picture a thin man in a ragged straw hat glares belligerently at the camera.

Behind him, dressed in cheap, ill-fitting clothes and clutching an old paper

bag, his wife and three young children stand apart, round-shouldered, looking down at the

sidewalk or off to the side, anywhere but at the camera. They are waiting for the

shame to end. But it won’t.

What has changed?

Flash forward to 1997. Joel Sternfeld ‘s “A Man

Walking Home, Washington Market Park, NYC” shows a well-dressed

late-middle-aged black man standing by a lamppost in a lush city park in an

upscale neighborhood. The man leans back, smiling, balancing two shopping bags.

We see that he is next to a garden. Tomatoes are growing. A sunflower nods its

golden head. The man’s mood seems peaceful, friendly. After so many years, he looks like he feels

at home.

Joel Sternfeld,

A Man Walking Home, Washington Market Park, New York, August, 1997

What has changed?

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935”

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935” Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

Mitch Epstein, Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983

Mitch Epstein, Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983