"Man and boy," Roger Mayne, All rights reserved

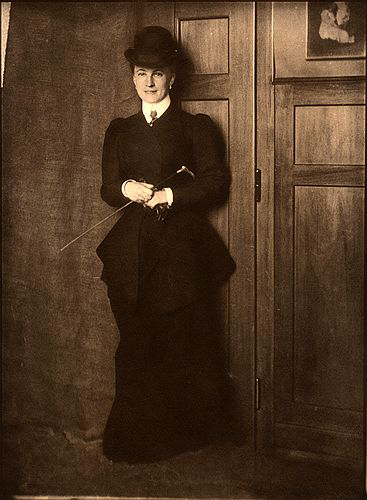

Now 83, Roger Mayne is a Brit who made his name photographing in working class slums in London and other British cities in the 1950s and 60s. Shooting in black-and-white with a small camera, he worked exclusively in a few chosen streets, which he visited over and over, becoming well-known enough to be ignored. Mayne describes his approach as “…visual rather than storytelling” and himself as “… a documentary rather than a journalistic photographer.” This seems right. His best pictures, though deeply grounded in a specific time and place, are Cartier-Bresson-like “decisive moments,” presented in universal human terms.

In his pictures Mayne’s sympathies are clear, but , ironically,

his elegant high-contrast shots often take their power from the very scarcity

that makes poor people poor. For

instance, Mayne frequently makes use of the clean converging lines of an empty

street and identical flats to give depth to foreground figures. With no cars or buses, no fruit stands,

not even trash bins to clutter the view, these stripped-down black-and-white

vistas have an undeniable graphic appeal (Bill Brandt used the same trick). But, in fact , no stuff means no money

-- poverty. These neighborhoods

are economically depressed. Should

they be aesthetically pleasing?

In this show Mayne’s principal subjects are children and adolescents . American

viewers will think immediately of Helen Levitt, who, during the same period, similarly

turned her lens toward children at play in the poor sections of New York City. At

that time, before TV had conquered everything, neighborhood streets in both

British and U.S. cities functioned as public living rooms and playgrounds. Both Mayne and Levitt saw the visual

opportunities and treated the communal street as a stage on which anything

could happen. Yet, looking at the two bodies of work, the British and American streets come across very differently. Was it that the two

cultures were that different? Or did the two photographers see the street life of

their subjects in fundamentally different ways?

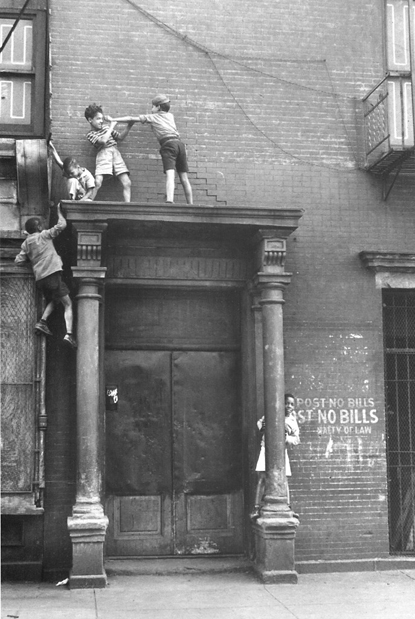

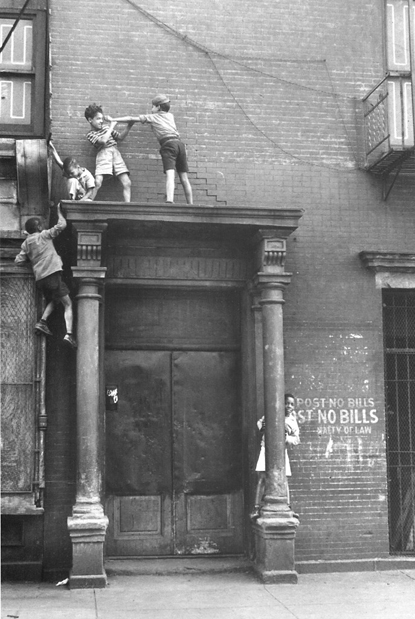

"Boys playing, NYC," Helen Levitt, All rights reserved

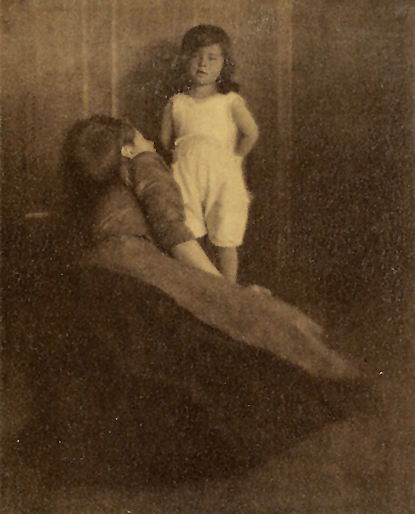

Many of Levitt’s New York pictures, for instance, have a wild, anarchic edge never glimpsed in Mayne’s work. Her children at play in Hell’s Kitchen or Harlem are making up the rules as they go along, broadcasting chaos and sometimes violence (along with joy) into cityscapes boiling with conflict. It’s possible that Levitt was only able to capture these moments because she was willing to shoot like a stranger – sometimes more like a spy – gladly tolerating suspicion and ostracism for a chance at life in the raw. In any case, her children are often fierce. They seem intent on testing limits. They give the razzmatazz to all comers. By contrast, Maynes seems to have gone after– or at least documented – something much more conservative. His West London or Battersea kids are tough all right. They have dirty faces and wear old shabby clothes; they smoke cigarettes almost out of the cradle. Yet their clothes are a kind of sober poor child’s uniform – the boys in stained suit coats, pants and caps, the girls in frayed but respectable dresses and sensible coats. Both sexes ride bikes for transportation, not pleasure. And their games, though boisterous, are deeply traditional – from medieval battles fought with construction-scrap swords and shields to cricket, soccer and marbles to mother-may-I? and hide-and-seek. If there is anger in these children, Mayne’s photographs don’t show it.

"Girl, Southam Street," Roger Mayne, All rights reserved

I wonder why. Anger isn’t visible in the children’s parents either, although a certain stoic wariness is detectable. It’s possible Mayne concentrated on photographing the young people because their parents discouraged his attentions (one marvelous exception shows a man in the street conducting an imaginary symphony for the camera; I’m guessing he’s gloriously drunk). Found almost always in the background or on the margins, the grown-ups are properly deferential (Mayne was an Oxford man) but not warm. They have been through a terrible war after all – and now they face unemployment and poverty. When most of these pictures were made, the horrors of the Blitz were more than 10 years in the past, yet little or no change had been delivered to the poor. Mayne’s middle-aged subjects may have wanted to believe in the sturdy, traditional England of “Keep calm and carry on.” But – from the discreet evidence of these pictures -- the old slogans were wearing thin.

"Boys playing, NYC," Helen Levitt, All rights reserved

Many of Levitt’s New York pictures, for instance, have a wild, anarchic edge never glimpsed in Mayne’s work. Her children at play in Hell’s Kitchen or Harlem are making up the rules as they go along, broadcasting chaos and sometimes violence (along with joy) into cityscapes boiling with conflict. It’s possible that Levitt was only able to capture these moments because she was willing to shoot like a stranger – sometimes more like a spy – gladly tolerating suspicion and ostracism for a chance at life in the raw. In any case, her children are often fierce. They seem intent on testing limits. They give the razzmatazz to all comers. By contrast, Maynes seems to have gone after– or at least documented – something much more conservative. His West London or Battersea kids are tough all right. They have dirty faces and wear old shabby clothes; they smoke cigarettes almost out of the cradle. Yet their clothes are a kind of sober poor child’s uniform – the boys in stained suit coats, pants and caps, the girls in frayed but respectable dresses and sensible coats. Both sexes ride bikes for transportation, not pleasure. And their games, though boisterous, are deeply traditional – from medieval battles fought with construction-scrap swords and shields to cricket, soccer and marbles to mother-may-I? and hide-and-seek. If there is anger in these children, Mayne’s photographs don’t show it.

"Girl, Southam Street," Roger Mayne, All rights reserved

I wonder why. Anger isn’t visible in the children’s parents either, although a certain stoic wariness is detectable. It’s possible Mayne concentrated on photographing the young people because their parents discouraged his attentions (one marvelous exception shows a man in the street conducting an imaginary symphony for the camera; I’m guessing he’s gloriously drunk). Found almost always in the background or on the margins, the grown-ups are properly deferential (Mayne was an Oxford man) but not warm. They have been through a terrible war after all – and now they face unemployment and poverty. When most of these pictures were made, the horrors of the Blitz were more than 10 years in the past, yet little or no change had been delivered to the poor. Mayne’s middle-aged subjects may have wanted to believe in the sturdy, traditional England of “Keep calm and carry on.” But – from the discreet evidence of these pictures -- the old slogans were wearing thin.

Mayne continued to work in the British streets through the

early 60s, capably depicting the teddy boy subculture that rebelled against the

austerity of working class life. But his documentation of British life seems to

have stopped there. By the

mid 60s, Mayne had begun to travel and concentrate on nature photography and

portraits of his growing children.

"Teddy boy and girl, Petticoat Lane, 1956," Roger Mayne, All rights reserved

"Teddy boy and girl, Petticoat Lane, 1956," Roger Mayne, All rights reserved

I wish he had continued. As an American boy, I was

fascinated in the early 60s by the Mods and the Rockers, “swinging London”and the mysterious

Flower Children. I remember

exactly where I was when I first heard the Beatle’s “I Want to Hold Your Hand”

on the radio. The British Invasion of rock n’ roll and blues and all that went

with it ignited this country and eventually the world. Yet no great

photographer recorded these changes in a way that matters.

Conclusion: we ought to appreciate pictures for what they

are, not criticize them for what they’re not. Roger Mayne made genial, accurate

– sometimes inspired -- pictures of a place which arguably spawned a global culture.

Good enough.