"Infidel," Tim Hetherington, All rights reserved

"Infidel," Tim Hetherington, All rights reservedDirectly across from the entrance to AIPAD 2012, a wall of large color prints by photojournalist Tim Hetherington shows young American soldiers in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley in 2011. Pictured sleeping in their bunks or trying to relax between battles, the (all-male) soldiers are young, fit & invariably shirtless. They wear camouflage pants and boots and sport lurid tattoos – one, in purple, says “Infidel.” The soldiers radiate a slightly dinged-up, bad-boy quality that reminded me, in spite of myself, of meticulously rough-looking ad shoots for jeans by Levi or Diesel.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Hetherington (who, soon after leaving Afghanistan, was killed covering the overthrow of Quadaffi) made these pictures as part of a very different story. Even a cursory glance at his Afghan pictures from Korengal reveals a full awareness of how murderous and confusing the conflict was for these young Americans. In their frontier outpost, always under attack, the men responded by closing ranks and projecting attitude and fierceness outward. As presented by Yossi Milo, who reportedly took over Hetherington’s estate after his death, this context is absent. The men here are warrior beefcake. Their war has become a brand.

Perhaps there’s no point of complaining about sales people trying to sell. But what exactly are they trying to sell here?

In 2012 the AIPAD galleries in general offered a great number of unstaged pictures. For instance, I saw work everywhere by the great photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson, who died in 2004. His work was crisply printed, matted, mounted and priced at about $15,000. But I noticed something I hadn’t seen before. Every Cartier-Bresson picture featured an authoritative signature in black ink on the margin of the print. Many of the mattes even had neat windows x-actoed out to exhibit the master’s name. They were standardized.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, All rights reserved

Henri Cartier-Bresson, All rights reservedIt’s true that Cartier-Bresson himself wasn’t very interested in the printing and presentation of his pictures. His famous quote,“Hunters, after all, are not cooks,” expressed his point of view. But there’s something sad about the way his brave, humane work seems to be aging. As witnesses die and passions fade, the events he photographed become, more and more, the pictures he made of them. Increasingly aestheticized and commodified, these moments become the elegance and style of Cartier-Bresson’s rendering. The jolting heartbeats that inspired the pictures are going.

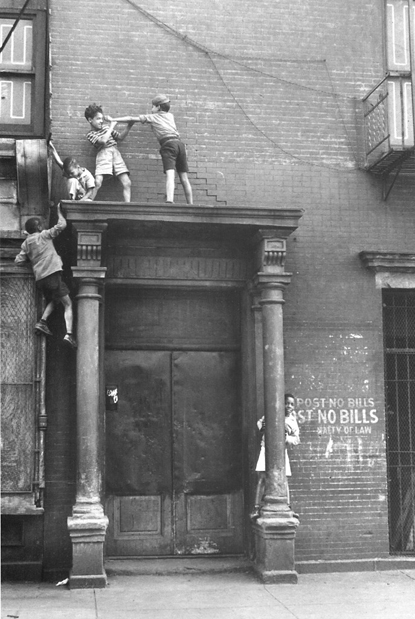

This AIPAD, in fact, convinced me that the black-and-white photographs of the Leica generation that included Cartier-Bresson – roughly from Andre Kertescz to Garry Winnogrand –are the new American canon. Included in this increasingly collectible category I saw prints by Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, Helen Levitt, William Klein, Eliot Erwitt , Mary Ellen Mark and others.

Perhaps it’s time for this to happen. Though some photographers will always choose to shoot in black and white for its matchless abstract and metaphorical power, it has now become, after all, a historical process. Yet something is indeed lost as black and white images move slowly away from the mainstream into the realms of art and scholarship.

The most expensive black and white pictures from this group were shot by the unsentimental outsider Robert Frank, whose star continues to rise with current street photographers. Perhaps today’s shooters, with their ubiquitous digital SLRs, sense in Frank a combination of determination and despair they also feel. “We are driven to do this work, yes, but, really, what’s the point?” they ask. Does the seemingly timeless success of Frank’s images give them any answer?

Most of Frank’s work at this AIPAD was beautiful, but the prices were high even for less-than-stellar work. I saw an uninteresting 8 x 10 shot of two couples on a bench in a Reno marriage mill (from the same take as the more famous shot of one couple on the bench) selling for $125,000. A dark print from 1951 titled “London Bankers” went for a princely $250,000. Even more surprisingly, a truly bad print -- a 1955 image titled “Coney Island,” was so muddy and flat any good printer would have thrown it out (and Frank had a good one, Sid Kaplan). The print was priced at $50,000. Rock bottom for the new Frank.

"Cab Culture," Ryan Weideman, All rights reservedHere’s a quick list of goodies you could have brought home from AIPAD 2012:

"Cab Culture," Ryan Weideman, All rights reservedHere’s a quick list of goodies you could have brought home from AIPAD 2012:Portraits of Frida Kahlo by Nicholas Murray in black and white and carbon print color from her 1939 trip to New York City. Winter Works on Paper: $1,500 for the black and whites; $6,000 for the color.

From four different galleries, virtually identical Ansel Adam’s “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, 1927.” Approximately $20,000.

Taxi driver/photographer Ryan Weideman’s in-cab portraits of the famous or merely weird. My favorite, “Salsa Ride With Salsa Betty,” from 2002. Bruce Silverstein.

Wonderful 1950 nude from Weegee the Famous, who apparently cut up the negative to insert a tilted third eye into the middle of the model’s forehead. Henry Fieldstein, $6,500.

A miserably anxious Janis Joplin sitting backstage clutching her pint of Southern Comfort. By Jim Marshall, $9,000.

“Jewelry Store Window,” Andy Warhol, black and white. Looks exactly like the proud submission of someone taking their first photo class. Erick Franck, $9,000.

Notable omissions: The Chinese, the French and the Japanese were there. Where were the Germans? There was no August Sander but also no Loretta Lux. Perhaps Andreas Gursky wasn’t there because the Park Avenue Armory was too small. Oh well, maybe next year.