Douglas Gayeton, All rights reserved

We celebrate iconic photographs that seem to encapsulate an event or era, but in fact they almost never do. Dorothea Lange's wonderful portrait of a migrant mother & two daughters from the Depression, for example, was true to the moment in which it was made; but the passage of time has turned it into a kind of history-lite icon for modern viewers. Lange's picture is only one facet of a complex reality, and most of us know it; but her unforgettable image becomes a compact takeaway version of the Depression that's hard to resist. We allow this perfectly defined moment -- worried mother, unhappy kids -- to stand in for the whole.

In the same way, pictures of our ancestors in the family album-- posed unsmiling in their Sunday best against studio backdrops or the old homestead -- misleadingly suggest lives devoid of laughter or passion. Do we really believe that everyone born before cheap, universal photography became available was frozen & grim ? Probably not, if we think about it. Yet we tend to accept these likenesses as true representations of their world.

Douglas Gayeton confronts this problem in his series, "Slow: Life in a Tuscan Town," showcased in an exhibition, reception & book signing this Monday (Nov. 2) at Clic Gallery, 255 Centre St. (corner of Broome). How can a single unchanging image on paper represent ceaseless changes over time? How, especially, can moment-freezing photographic "glimpses" convey Gayeton's subject --"slow life..." the myriad, small-scale, subtle changes & behaviors that add up to life in a traditional rural Italian village? The way of life Gayeton seeks to record follows unchanging cycles, yet is endlessly improvisatory. It is hundreds, maybe thousands of years old -- and may disappear within the decade. How can Gayeton make us see this as a potential tragedy & not as just another earthy/exotic variant of the "family of man?"

Douglas Gayeton, All rights reserved

Gayeton is hardly the first to try to use, & at the same time, springboard from, the literal realism of the still photograph. From its invention, photographers felt limited by the medium & sought to expand the form . Pictures sought to conquer time with lantern slides & zoetropes -- which ultimately became film. Magazines -- most notably Life -- combined carefully edited & captioned pictures with journalistic text to create seamless narratives that had a beginning, middle and end. Going in the other direction in their paintings, Picasso, Braque & the Cubists broke narratives into multiple viewpoints, perspectives & sizes -- exactly like the output of a typical day with a camera.

Today, artists like Duane Michaels, Paul Graham (who I wrote about here) and dozens of others continue to use unphotoshopped images to tell -- & subvert -- stories.

"Chance encounter," Duane Michaels, All rights reserved

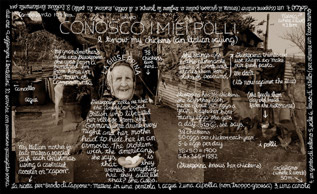

Gayeton's solution is what he (ambitiously) calls "flat film." The technique -- which often combines key images over time from a variety of viewpoints with text that records its own layers of space & sequence -- is charmingly explained in this video. For the critic it remains only to judge whether the method is successful.

I'd say it is, but with reservations. This show should be seen for its intimate pleasures as well as its satisfying scope. Gayeton has broken down the wall of strangeness that usually rises between photographer and subject and placed us, the viewer, directly into a world we would otherwise never enter. At the same time he has managed a much larger view & made it clear that we lose this world at our peril.

My reservations: It may be good marketing to link Gayeton's work with the Slow Food movement (the book's introduction is by Alice Waters); but the association may also misrepresent the work. Anti-standardization or not, slow fooders necessarily deal in propaganda, &, to be effective, propaganda must always deal in cliches or near-cliches. Thus we have a rich sepia tone on every image in this series -- as though their elegiac, past-in-present quality might be missed. Similarly, Gayeton's written commentary on the photos -- a witty English-Italian mix of quotes, nicknames, birth dates, overheard anecdotes, recipes, directions to out-of-frame sites of local interest & so on -- is rendered in schoolboy cursive, every letter meticulously & slowly made. Is this really necessary?

Douglas Gayeton, All rights reserved

Similarly, I can't avoid recording my frustration with the amount of text covering some of these photographs. Witty or not, the writing sometimes blocks the information, not to mention the beauty, one can get from the pictures alone. Gayeton's pictures are stunning in their own right. To me at least, they are as moving a testament to the vanishing way of life he loves as anything he or anyone could write. Couldn't some part of the text, I kept wondering, have gone elsewhere?

No comments:

Post a Comment