"St. Cloud," Eugene Atget, All rights reserved

"St. Cloud," Eugene Atget, All rights reservedFrom 1898 to 1927 a modest handmade sign, “Documents pour Artistes,” hung outside Eugene Atget’s small one-room studio in Paris. In those days passersby would have read the sign without irony, but now it has become the title of a major

show of Atget’s photographs at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA).

Would Atget appreciate the joke? He made his living systematically photographing the old quarters of Paris on spec, then selling his “documents ” as mounted prints. According to his own description, Atget’s subjects included, in part “… historical and curious houses, fine facades and doors, panellings, door-knockers, old fountains, period stairs … and interiors of all the churches in Paris.” His clients were architects, stone masons, iron fabricators, stage designers, archivists and painters looking for source material. Few, if any, of these visual professionals had any idea they were acquiring art.

More than a century later Atget’s pictures evoke a very different response. Led by the late MOMA photography czar and critic John Szarkowski, many art historians now regard Atget as the founding father of modernist photography. “His work seems to represent a qualitative change in the history of photography,” Szarkowski wrote. In another essay he called Atget “… a photographer of such authority and originality that his work remains a bench mark against which much of the most sophisticated contemporary photography measures itself.”

"Mannequins," Eugene Atget, All rights reserved

"Mannequins," Eugene Atget, All rights reservedIf we go by the testimony of the photographers who came after Atget, that’s certainly accurate. Berenice Abbott -- who first “discovered” and later promoted his work -- as well as Walker Evans, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Lee Friedlander, among others, have claimed his influence. But it’s worth remembering that, during all but a few months of the 29 years Atget worked alone on his grand project of photographing Paris, his pictures were so stubbornly different from the soft-focus allegories of the prevailing pictorial style that they were literally not seen – except as record-keeping – by all but a few of his contemporaries.

I go on about this because such “ugly duckling” stories – with their eventual transformations into artistic swans -- happen rarely. Rarely in one lifetime anyway. Interestingly, during the 1880s, also in France,

a similar story was playing out in European painting. In Paris and then at Arles, Vincent Van Gogh’s work was all but universally mocked as primitive and ugly. It wasn’t until some years after his death that his paintings were finally understood – first by German expressionist painters -- and later by the general public, worldwide. Ultimately, as we know, they were enshrined.

We don’t really know much about Atget’s life, as Szarkowski repeatedly pointed out; but we do know that, like Van Gogh, he possessed an unshakeable dedication to his own way of doing things. “He had very personal ideas on everything, which he imposed with extraordinary violence,” wrote Atget’s best friend, Andre Calmette, in a letter to Abbott. “He applied this intransigence of taste, of vision, of methods, to the art of photography and miracles resulted.”

"Marchand abat-jours," Eugene Atget, All rights reserved

"Marchand abat-jours," Eugene Atget, All rights reservedA visitor to Atget’s MOMA show feels this radical purity from the moment he or she encounters the eye-level rows of identically sized and mounted prints filling two rooms. Atget used a tripod-mounted view camera to make 24 X 18 cm glass negatives. After they were developed, he made albumen or gelatin silver contact prints by sandwiching them against same-sized light-sensitive paper and exposing it to sunlight. This process never varied, though photography equipment was making rapid technical progress throughout the period (

Andre Kertesz, for example, was in Paris in the 20s, shooting with a Leica).

Perhaps Atget’s unchanging way of working – and his refusal to crop pictures during the print-out process -- helps explains his faultlesscompositions. Abbot’s observation that “he knew exactly where to put the camera,” though deceptively simple, says a lot after all. But nothing really -- short of speculating about some sort of instinctive genius – explains Atget’s unerring ability to balance shapes, tones and, indeed, meaning in perfect momentary equipoise. His visual arrangements are never fussy. They are simply there, perfect in their worldly imperfection, proclaiming no bias or aesthetic theory. They feel as though they come more from Atget’s body than his mind.

"Jardins de Luxembourg," Eugene Atget, All rights reserved

"Jardins de Luxembourg," Eugene Atget, All rights reservedThis lack of bias is apparent too in Atget’s acceptance of subject matter. It’s not a question of moving things in or out of the frame – as far as I can tell, Atget doesn’t. For him, a discarded rag or broken, fallen branch simply becomes part of the picture. But Atget goes beyond that. He allows messiness and confusion into his pictures as graciously as he accepts the clean, well-defined lines and shapes that any landscape photographer would love.

All this can be seen in Atget’s masterful final series of the once-grand estate park at Sceaux near Paris, which this exhibition movingly showcases. Decaying and overgrown, Sceaux was scheduled to be renovated into a public park in 1925. Atget wanted to photograph it before that happened. He began in March when the trees were bare and made his last picture in the full bloom of June.

"Park de Sceau, 1925," Eugene Atget, All rights reserved

"Park de Sceau, 1925," Eugene Atget, All rights reservedWe have to imagine this part: An old man (he had less than two years to live), Atget rises before it is light and gathers his tripod, camera and glass negative plates – perhaps 30-40 pounds of equipment. He is going to the park at Sceaux, and he prepares alone. His “amie” and common-law wife for 30 years, a woman named Valentine Compagnon from his time in the theater, is unwell and will die within the year. Atget makes sure she is comfortable, then leaves and rides the Parisian trams to the old estate. Carrying his gear -- he has carried it for decades -- he walks into an ancient park, in which magnificent marble terraces and statuary are mouldering in dark woods beside pools filling up with mud.

Atget finds his first location of the day. He knows what to do, and it makes him happy to do it. He gets ready to expose a negative. His pictures will be like poems.

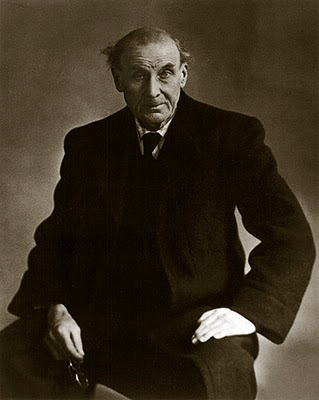

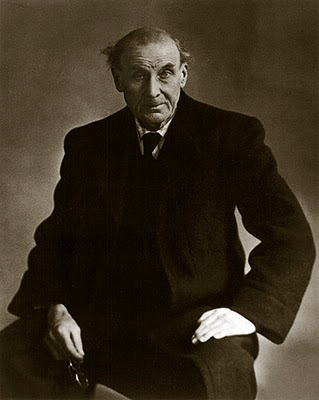

Berenice Abbott, "Eugene Atget, a few weeks before he died," All rights reservedThis review also appears in The New York Photo Review.

Berenice Abbott, "Eugene Atget, a few weeks before he died," All rights reservedThis review also appears in The New York Photo Review.

More on Eugene Atget: "Signs, signs -- everywhere a sign."