"Police Work: Man restrained by two policemen," Leonard Freed, All rights reserved

Two uniformed white cops hold down a struggling black man on the hood of a car. What does this photograph tell us?

The answer of course depends on who is looking. Are the cops heroes, risking their lives to hold back a crime wave? Or are they brutal occupiers, imposing the power of society’s elites on an oppressed minority?

In 1972, when photographer Leonard Freed assigned himself the task of documenting the working life of the New York City Police Department, this was a volatile question, one that could – and did – spark fights at bars and dinner tables all over the city.

According to a wall text at Freed’s “Police Work” show at MCNY, New York in the 70s was "…marked by heated controversies surrounding the NYPD – over civilian review of police misconduct, scandals within the department, soaring crime rates and the tension inherent in policing a city increasingly divided by race, class and the political upheavals of the Vietnam era.”

Freed was well suited for this controversial project. Born to a working class family from Brooklyn, he was a Magnum photographer who had shown considerable insight and sympathy for minorities with his 1967 book Black in White America.He was also fair-minded about cops. “They are not psychiatrists, they are not lawyers, they are not doctors,” he remarked. “They are blue-collar workers. ”

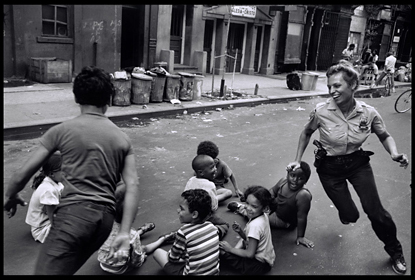

"Police Work: Policewoman with kids," Leonard Freed, All rights reserved

The photographs in this show reflect Freed’s even-handed approach. From a gang of cops tackling an anti-war demonstrator (one of the cops applies a choke hold) to a pretty blonde policewoman cavorting with neighborhood kids, the full range of “the job” is covered. To my mind, it is sometimes too well-covered. With seven years of contact sheets to choose from, the curators sometimes show us dutiful pictures of police process.A forensic expert in a lab coat “… studies the marking on a spent bullet; ” a young woman points to a police artist’s sketch …the composite of a suspect…” These are check-off-the-box pictures for bureaucrats.

Perhaps they are included to lower the show’s temperature. In the hyper-violent city of those years, Freed was often first to arrive, along with the police, at gruesome murder scenes . His pictures of these scenes (most viewable on the internet but not in the show) avoid the tabloid zest of his famous predecessor Weegee, but they are nevertheless ugly and disturbing . Only one is included in the exhibition -- an uncharacteristically neat visual narrative in which the victim is sprawled out-of-focus in the background and a till full of glinting coins protrudes into the foreground. About this picture Freed writes: “Homicide in a foodstore. The clerk was shot dead for the few dollars in the till.”

"Police Work: Precinct detective squad," Leonard Freed, All rights reserved

In general Freed’s work here is not inclined to visual homilies. His style is to get close, shoot without tricks, and let the photographs tell the story. In the hands of a brilliant and compassionate shooter like Freed, the technique works. These worldly, subtle, passionate pictures transport a viewer almost palpably into the life of a deteriorating New York City and its stressed-out inhabitants – on both sides of the law. They are well worth seeing.

Still, I had trouble committing myself to this show. Perhaps it was because the standard 8” x 10” and 11” x 14” black-and-white prints arrayed on the walls reminded me of photojournalism classes I had myself attended in the 1970s. I realized this show’s intentions – its rock-bottom faith in the power of honestly-made photographs to tell the truth – felt familiar. It was what we had all believed.

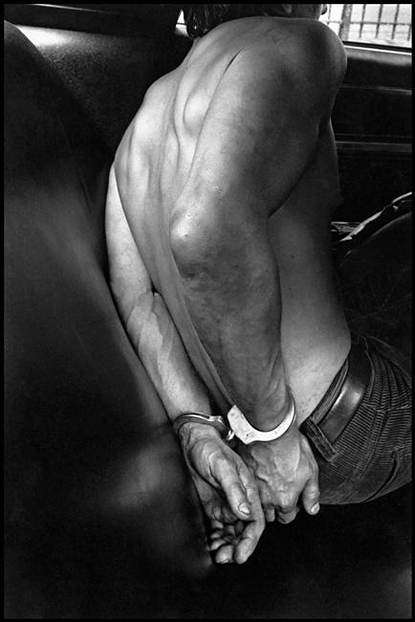

"Police Work: Arrested man in back seat," Leonard Freed, All rights reserved

But after Vietnam – and especially after the advent of digital cameras – many of us grew wary of photographic truth. The problem was not only the potential for technical manipulation of images. It was a new awareness of what is left out of the frame, left out of the edit – sometimes even by a person with the best intentions.

In fact, after seeing these pictures, I find I trust Leonard Freed. But can these pictures, in this place and selection and configuration, really tell the truth in 2012 about police work in 1970’s New York?

It depends on who is looking.

This review also appears in The New York Photo Review. Check it out.

More about Leonard Freed

4 comments:

Police are not racist, certain races feel a sense of entitlement towards crime because they are seen as individuals who are going to commit the crimes anyways. It is clearly flawed logic but the race of offenders is not up to the police but the offenders (and the family that raised and gave birth to such individual). I know more racist "colored" people than caucasian, what does that tell you?

In my review I don't say or imply that cops were/are racist. To my eye, neither does Leonard Freed. I was talking about the way honest pictures can be seen in various ways by various people, depending on their biases.

I've been a cop for 14 years. Fifth generation. It's a bizarre job, but one that I find myself not wanting to leave. Even when I'm totally disgusted. I own a copy of Freed's book "Police Work" (1980) and it isn't going anywhere. Personally I like the warts and all approach.

Jeff Cordell

Jeff, I agree with you.

Post a Comment