"Bombardopolis, Haiti, 1986," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Bombardopolis, Haiti, 1986," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

Alex Webb visits places to which he is instinctively drawn & walks around taking pictures in color with a small camera. He has not varied this simple method in over 30 years. He is, he insists, a street photographer, a wanderer at ground level, hoping to encounter “…the unexpected, the unknown, or the secret heart of the known … just around the corner.”

Despite this simple formula, Webb’s work from the late 70s to the present – collected in

“The Suffering of Light: 30 Years of Photographs” at Aperture Gallery -- is anything but simple. Made in Haiti, Cuba, Mexico, Congo, Turkey and other “places of cultural and often political uncertainty -- borders, islands, edges of societies … “, the pictures pay little attention to critical categories. They are loosely anchored in photojournalism -- Webb was elected to

Magnum Photos early in his career. But they also freely cross and re-cross the increasingly blurry frontiers between journalism, documentary and so-called art photography (Webb’s work has been a major force in blurring those labels).

Colors are the deeds

The show’s title, “The Suffering of Light, ” is taken from Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe’s lovely metaphor, “Colors are the deeds and suffering of light.“ To Webb this is more than just a poetic formulation. Like most photographers of his generation (he is 59) he started out shooting black-and-white. In 1975, a few years before he shot this show’s first picture, Webb tells us, he took a trip to Haiti that “… transformed me – both as a photographer and as a human being. “ After a few more experiences in the tropics, he knew he had to deal with “… the intense, vibrant color of these worlds … somehow embedded in the cultures … so utterly different than the gray-brown reticence of my New England background.” In 1978 he began to work almost exclusively in color and continues to do so today.

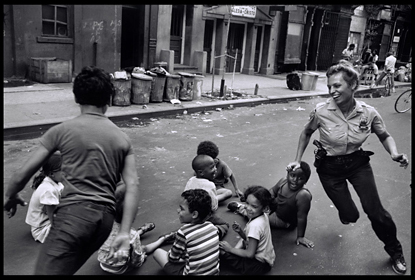

"Kampala, Uganda, 1980," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Kampala, Uganda, 1980," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

In the tropics Webb exposed

Kodachrome film to saturate colors as deeply as possible in the full blaze of the southern sun. In the strong light, shadows become a rich, impenetrable black. In Webb’s palette these blacks are a sort of primary color. Far from denoting a lack of information, black becomes a fierce presence. It seems to tear away whole sections of pictures and swallow their hues. In some pictures doorways – or gorges and caves –open into a world of black, which seems to spawn abyssal shapes and creatures that cross back into this world. Like Webb’s clamorous reds and sensual pinks, or his alienating purples and melancholy blues (other descriptions may apply), black is here much more than a color.

Kodachrome is of course famous for its colors. When Webb began to rely on it in the 70s, it was a relatively slow film (ASA 25, 64 and 200), very contrasty, that gave bright, warm colors without overdosing into electric pop. The only drawback was that it could only be developed using Kodak’s proprietary process at major labs or the Kodak company itself. As new slide films proliferated, Kodachrome became hard to find outside cities or college towns. In the 80s many Kodachrome users simply accepted Kodak’s

Ektachrome or the Fuji company’s

Fujichrome , both decent but inferior films that could be developed by anyone using the E-6 process.

"Gouyave, Grenada, 1979," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Gouyave, Grenada, 1979," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

Interestingly, Webb stuck to his artistic guns. When the last two Kodachrome films went out of production (ASA 200 in 2007; ASA 64 in 2009), they had long been available only through specialized sources. But Webb continued to use Kodachrome till the bitter end, sending his film to Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, Kansas, the last place to develop it.

Dwayne’s closed its processing shop on July 14, 2010. Webb is now experimenting with a digital Leica and other color films, both positive and negative (see

an interview about his recent work on Magnum Blog)

Thirty years of photographs

If this show is a retrospective of three decades, as its subtitle suggests, it’s remarkable that the passage of time is almost invisible. In poor streets around the world, it seems, 1979 is almost identical to 2009. Our much-vaunted digital revolution is nowhere to be seen, for instance; even styles of clothing and accessories have barely changed. The streets are full of the same old junk, the same worn-out furniture and broken concrete, year after year.

This may be an important truth. On the other hand Webb’s interests and style over the 30 years haven’t changed much either. We can perhaps read “Thirty years of photographs” as polite information, New England-style. This show is not the usual survey through time, designed to sum up an artistic journey as it unfolds. The summary here could feasibly read: Alex Webb found his work and figured out how to do it. Then he kept on doing it. (Good.)

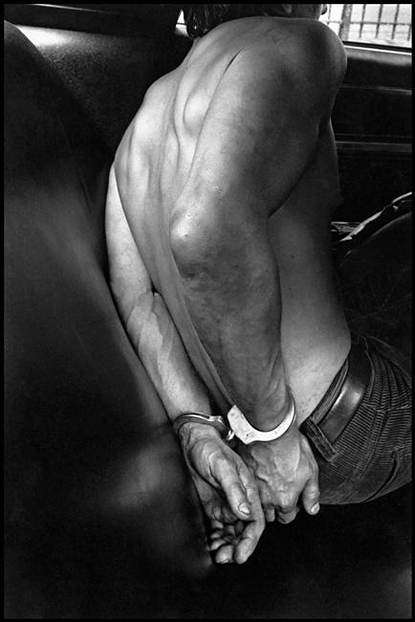

"Ciudad Madero, Mexico, 1983," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Ciudad Madero, Mexico, 1983," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

I’m not implying that Webb has exhausted – or even, as far as I know, fully tapped – the human or aesthetic preoccupations that drive him. Covering distant conflicts by turning away from the usual cast of “newsmakers” and concentrating on the ordinary people affected by those conflicts has helped pioneer an open-form version of photojournalism that helps ameliorate the endless, boring shots of politicians as well as the bloodless navel-gazing so characteristic of most contemporary photography found in galleries. Although Webb’s images may sometimes provide an indelible glimpse of a time and milieu, they are not essentially about historical events or even places. They take us to new worlds and give us new ways to see them.

Styling reality

Webb’s solutions to visual problems can seem prodigiously complicated. Often his pictures are divided and/or framed internally by trees, statues, lampposts, windows, doorways, blast holes -- any device that marks off distinct worlds. The created mini-worlds are often oblivious or contradictory to one another; they may exist at different depths – and so be bigger and smaller -- in the larger picture frame. They may sport jarring colors, wild and domestic animals, dancing people or desolate landscapes. They may all seem to be going in different directions.

"Tijuana, Mexico, 1999," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Tijuana, Mexico, 1999," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

Add to this Webb’s evident fascination with doubling devices – mirrors, shadows, reflective metals, paintings, posters, billboards, photographs, graffiti – and his openness to intrusions -- truncated signs, mysterious limbs – from the unseen, out-of-frame world, and these pictures are pushing at the very limits of chaos. Yet the images somehow hold together. At the show’s opening I heard a young woman say about one of the pictures: “It’s a collage!” “Yeah, but no one put

those pieces together,” replied her friend.” “No one

could have ever put those pieces together!” said the first woman.

She’s right. These may be the most compositionally complex photographs around that don’t depend on photoshop for their effects. In a way, looking at Webb’s pictures is like watching an old-fashioned magic show. What transforms sleight-of-hand into magic is the ineluctable reality of the hands, sleeves and coins that we try to follow with our eyes. Here it’s the un-fakeable reality of children, women and men – shown in ensemble – as they spin from exuberance to despair in the kaleidoscopes of poverty and upheaval. If we saw these people conventionally isolated, picked out and framed to receive our pity or our anger, the impact would not be the same.

Webb takes us as far as an outsider can go into these realities. Perhaps the complexity of the pictures gives us a glimpse into the everything-at-once, grab-it-quick-if-you-want-it experience of living with no safety net in the developing world. There is irony in the fact that such near-to-bursting compositions are often achieved by traditional strategies. Graceful S-curves and Z-scriptions lead our eyes into the picture space; shapes entice; edges direct or surprise; colors repel or caress and, in the end, everything somehow balances, even if a horizon is skewed or a person left floating at an odd angle in space.

"Saut d'Eau, Haiti, 1987," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Saut d'Eau, Haiti, 1987," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

It’s not reality. It's art.

What interests me about my own response is that I don’t find this artifice fussy or over-obvious. It’s because there is no corresponding attempt to stage-manage the meaning. These pictures avoid being didactic. They are what they are. In fact, after I have registered admiration at their mastery, they confound me more often than they explain. They evoke ambiguity – or sometimes laughter – instead of certainty. They might be lyrical or horrendous, but they rarely evoke a simple response. Like their form, the meanings of these pictures are probably multiple and certainly complex.

Dancing in the streets

I heard Webb tell a fan at the opening: “I never know if I got it or not.” He was referring to the improvisational way he makes many of his best pictures -- the jumping-in moment as he senses the parts coming together. We might call it the hunter’s moment. It is that instant when eye, brain and body align, adrenaline surges and the trigger finger begins to tighten. For Webb and other street photographers, by the time the shutter closes, reality has already become something else.

Did he get it?

Of course Webb never knows. Nobody working this way ever knows for sure. And, of all contemporary photographers, Webb may be the one who keeps the most visual balls in the air. (

Lee Friedlander loads up his frames similarly, but often with unmoving objects.) I’d argue that Webb’s particular genius as a street photographer lies in two things: 1) an extraordinary ability to imagine/see pictures in the swirling midst of complex, unscripted reality and 2) unusual skills for capturing those pictures in visually coherent compositions.

"Nueva Laredo,Mexico, 1993," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Nueva Laredo,Mexico, 1993," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

What goes into these skills? Well, not to be glib -- everything really. Everything read, seen, heard and experienced in a photographer’s life goes into his work. In addition, the photographer needs intuition, another gift. And he needs physical skills – not much discussed, but absolutely essential – to move to the right spot and shoot at the right moment while all the other elements in the picture are also moving.

In his book

Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences,

Howard Gardner describes spatial intelligence – very roughly, the ability to manipulate spatial information as mental imagery – and bodily-kinesthetic intelligence – again roughly, the mastery of one's own physical movement, as exemplified by mimes, dancers and athletes. It seems to me that these ideas also describe what great “walking photographers” like

Andre Kertesz,

Henri Cartier-Bresson,

Garry Winnogrand and

Alex Webb actually do.

For photojournalists, shooting pictures has always been, first and foremost, about getting to the scene. For Webb and others who step on and off the photojournalism bus – who choose subjects for personal rather than news-driven reasons, come back to shoot over and over again and abandon the pretense of reportorial objectivity – it's like playing an old game in a brand new way. In this respect, it's interesting that in his book Gardner chose legendary Canadian hockey player

Wayne Gretzky to illustrate bodily-kinesthetic intelligence.

A Canadian friend once described Gretzky to me as. “Small for the pros, skinny, not a fast skater, not a great slap shot…and the best who ever lived.”

Hockey journalist Peter Gzowski explained it more technically: “Sometimes [Gretzky] will release the puck before he appears to be ready, threading the pass through a maze of players precisely to the blade of a teammate’s stick, or finding a chink in a goaltender’s armor and slipping the puck into it … before the goaltender is ready to react. What seems like luck or magic is neither. Given the probable movement of the other players, Gretzky knows exactly where his teammate is supposed to be.”

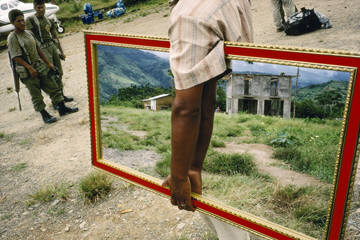

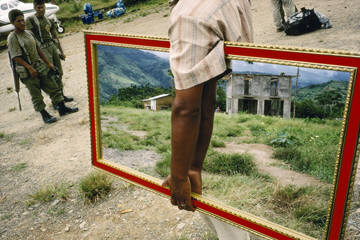

"Palmapampa, Peru, 1993," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Palmapampa, Peru, 1993," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

From the evidence of these pictures, I’d suggest that Webb possesses a similar sort of talent. Seeing is one thing, but street photography also depends on highly-developed instinct, sure-footed physicality and perfect timing. Making his way down a street in the developing world, let's say -- physically “threading through the maze,” intent on “finding a chink” -- Webb is invariably an outsider. At least one set of eyes, possibly a dozen, are watching him carefully. He’s waiting for something to happen. What’s going on? What’s important? He’s taking in light, color, smells, shapes, the sky, buildings, signs, animals, machines. He’s registering the people as they move around him. Is that a picture? He can shoot more than one frame, but not many more, and maybe only one without changing the subtle mood he is trying to capture... No, it's gone. He keeps walking.

This is very different from a photographer shooting in his home town or suggesting changes to a model in front of his lens. Walking and photographing on the street in another country, another language requires an unusual trust in one's own inner resources. As well-known street photographer and teacher

Tod Papageorge describes the process. "You walk out the door and—bang!—like everyone else, you're part of the great urban cavalcade...You're carrying an amazing little machine that, joined with a lot of effort, can pull poetry out of a walk downtown. All of the failed pictures you've ever made, all of the other photographs you've ever loved, even songs and lines from poems walk with you too, insinuating themselves into your decisions about what you'll make your photographs of, and how you'll shape them as pictures."

For over 30 years Webb has been brilliantly practicing his own version of living by his wits. The pictures in this show demonstrate a steadfast commitment to his ideas of what's important, what's true and what's beautiful. This reviewer agrees with him on all three counts. May he continue to walk and shoot pictures for another 30 years.

"Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1979," Alex Webb, All rights reserved

"Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1979," Alex Webb, All rights reserved