From "William Eggleston's Guide," All rights reserved

Panned as vulgar & banal in 1976, Eggleston's work is now generally, if not universally, acclaimed. But I've noticed that viewers who agree on the importance of his work still seem at odds about its intentions. Many see -- many photographers try to imitate -- a certain deadpan irony they believe they see in his pictures. In their view Eggleston's celebrated tricycle, made monumental as a low-angle closeup (above), might be seen as his urinal a la Duchamp, his way of sending a pretension-deflating message -- perhaps, "Banal is boring, but boring is honest (get over it)."

This is a misreading. In fact, Eggleston's pictures are never boring. There's a pulse of surprise, even astonishment, in every one of them, no matter how quirky or humble the subject. Eggleston's distinctive compositions & strong, occasionally hallucinatory, color underline the point -- these are not family snapshots.

From "William Eggleston's Guide," All rights reserved

Except -- in a way -- they are. The suspicion of empty amusement on the photographer's part probably persists because some viewers can't accept such commonplace subject matter as serious. For one thing, many of the pictures are located in the suburbs, a place our liberal culture regards with contempt . Yet Eggleston, paying no attention, finds there, as he seems to find everywhere, what The New Yorker's Peter Schjedahl calls "epiphanies in the everyday."

"Backyard barbecue," William Eggleston, All rights reserved

John Szarkowski, the photographer & critic who, as director of MOMA, famously championed Eggleston's work, wrote about the strange, often dark currents that swirl around these ordinary, middle-class subjects: "We have been told so often of the bland, synthetic smoothness of exemplary American life, of its comfortable, vacant insentience, its extruded, stamped and molded sameness... that we have come half to believe it, and thus are startled and perhaps exhilarated to see these pictures of prototypically normal types on their own ground...who seem to live surrounded by spirits, not all of them benign."

From "Wiiliam Eggleston's Guide," All rights reserved

Eggleston's unstudied equanimity, his conviction that each subject is as important as every other subject -- expressed in this show's title, "Democratic Camera" -- is not disturbed. The intensity of his vision seems to combine strong attraction with a natural tendency toward detachment. "I think I had wondered what others see -- if they saw like we see," Eggleston once remarked. "And I've tried to make a lot of photographs as if a human did not take them. Not that a machine took them, but that maybe something took them that was not merely confined to this earth."

A little spooky (possibly part tongue-in-cheek), but such aesthetic distance does not imply lack of feeling.

From "William Eggleston's Guide," All rights reserved

Take the shot that opens the Whitney show, a big tawny hunting dog lapping muddy water from a pothole on an unfinished country road in Louisiana (above). To my northern city eye it's an exotic image of an insular Southern, masculine world. But could the impulse to take it have been a kind of joke? No doubt Eggleston is well aware of the Southern mythology that goes with such a picture -- the guns & bourbon & big roomy muscle cars racing on dirt roads through the cotton fields. Is he playing with my middle-aged male literary head here? Is he invoking an updated Yoknapatawpa County?

Eggleston won't tell us. He won't talk about his pictures, except in a cursory way. But after seeing the Whitney show, I'm convinced visual cleverness & double meanings are not very important to him. To me the central truth of the picture comes to this: Eggleston loved the dog. He may or may not have known her before that moment or stood on that road or had any connection to the car or house in the background. But I believe he loved the dog, her rich colors & insouciant grace & that it was this-- some kind of romantic intuition of pure beauty -- that compelled the picture.

I find it significant that Eggleston never feels the need to explain his pictures. Even at their strangest & most startling --- shots of the inside of his oven or shoes tumbled together with an old gilt frame underneath his bed -- they are not made to comment or to illustrate. At their best they are complete in themselves. Form & content are fused & thus inexplicable in words. Szarkowski again has it right when he says the work "...leads us away from the measurable relationships of art-historical science toward intuition, superstition, blood-knowledge, terror and delight." (Szarkowski's complete essay is here.)

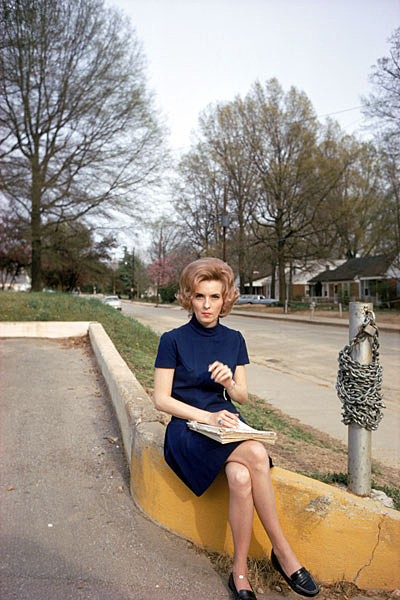

From "10 Dye Transfer Prints, V2," William Eggleston, All rights reserved

Some of Egglston's pictures seem so unhesitating, they suggest little or no gap between romantic perception & its realization. It's as though he already knew certain pictures were his -- that they fulfilled some private meaning -- before he ever saw them. Take the redheaded girl at the snack stand (above). Yes, this picture could be about the lost salvation of youthful beauty. Or it could simply be that the young girl's unearthly red, red beautiful hair -- the way it pours through the frame -- needed to be acknowledged & preserved as a sort of private miracle.

From "Troubled Waters," William Eggleston, All rights reserved

In its 2nd sentence, Wikipedia's article about Eggleston states: "He is widely credited with securing recognition for color photography as a legitimate artistic medium to display in art galleries." I've read dissenting opinions that very properly want to include in this achievement great color artists like Eliot Porter, Ernst Haas, Joel Meyerowitz, Helen Levitt & others. However, having seen the Whitney show, I see why the honor went to Eggleston. The color in these pictures left me staring, slack-jawed -- not because of the brilliance of its hues (any photoshop amateur can produce that) -- but because of their richness & subtlety. Such colors may exist in the real world (& we don't see them) or they suggest colors we are unable to see. In either case, they seem perfectly calibrated to enhance, rather than overwhelm, the work's essential naturalism.

Why is Eggleston's color so different from other photographers? In the late 60s & early 70s he was running around shooting slides like thousands of others. He began experimenting with color-dye transfer prints, a difficult & expensive process that allowed him to saturate certain colors without changing others. "I don't think anything is as seductive as dyes," Eggleston concluded. He's right, and seduction is the key word. Dye-transfer printing allows Eggleston to access what Schjedahl calls, "his great subject...the too-muchness of the real."

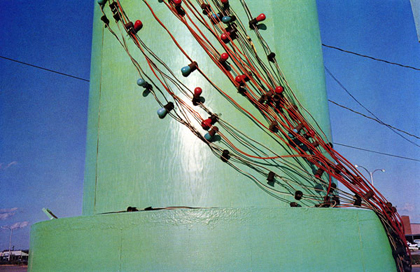

From "Los Alamos," William Eggleston, All rights reserved

It almost goes without saying that the color in the images I've downloaded here bears little or no relation to the color in the prints at the Whitney or to Eggleston's artist-approved books, monographs, portfolios or museum catalogs. For me, focusing my view on Eggleston's rich colors -- forgetting the rest of the picture -- induced a kind of deeply pleasurable trance. But, alas, don 't try it at home.

From "Kyoto," William Eggleston, All rights reserved

There's much more to this show. For instance, Eggleston's 1974 black-&-white video, "Stranded in Canton," plays continuously in one of the back rooms (I wrote about it here). The video, chronicling wild times in the dive bars of Memphis & New Orleans, is another aspect of the artist -- the Eggleston who lived with Viva at the Chelsea Hotel & ran with companions like Dennis Hopper. I suspect there's more to come.

In the meantime, see this marvelous show.

9 comments:

Okay, you've put this show on my list to see in January. Thanks for the review and insights.

Wonderful review, Tim. I'm hoping to get up there in either January or February to see the show.

Thanks for the review, Tim. We went last Wednesday morning, and the Whitney was fairly quiet, so we were able to take our time. The show is great, I'd recommend it highly.

There were quite a number of pieces I had never seen before, which was quite a surprise.

Happy holidays!

Andrew

I understand the Whitney has also published a terrific catalog for the show, a valuable tool for those of us out in the hustings.

Chris, Good point! For those who want to, it's at http://whitneystore.stores.yahoo.net/wiegdeca1.html.

Wonderful, illuminating post, Tim! Many thanks, and Merry Christmas to you!

Fabulous post! Just stumbled across it as I searched for more information regarding Mr. Eggleston; I'm ashamed to say I'd never heard of him until this afternoon. Now I'm entranced. Thank you!

Very beautiful pictures.

Just saw the exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago and was blown away. I blogged about it today and linked to your blog post. Excellent piece and great blog.

Post a Comment