As a photography student at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the 1970s, Thomas Struth learned to create

big, highly detailed pictures with his classmates – now photographic luminaries

-- Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff and Candida Hofer. At the time their teachers, the

legendary husband-wife team, Bernd

and Hilla Becher, taught a

technically rigorous system to “objectively” document disappearing German architecture.

According

to the Becher system, subjects must be captured serially with a large-format camera using black-and-white

film under a cloudless sky. All subjects must be shot from uniform distances

and heights, printed with medium contrast at a prescribed size and shown

together to facilitate comparison.

In his current show at the Met we see Struth’s homage to

this exacting style -- a wall-sized grid of black-and-white prints showing

well-known New York City intersections in 1978. Older New Yorkers may treasure or

rue these pictures as memories, but the more salient point is that, soon enough,

nobody will be alive to remember them. Still, there is much to admire in the

way the pictures treat, not only the streets and buildings , but everything -- every

parked car, overloaded trash can and

random walking-through-the-shot human -- with exactly the same crisp, non-judgmental

clarity.

"Crosby Street, Soho, 1978," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

This is Struth’s first major project. Afterward, his career moves on fast. Without abandoning the discipline and technique he has acquired from the Bechers, he begins to take on large ideas and issues. It is his willingness to do so that animates this show.

"Crosby Street, Soho, 1978," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

This is Struth’s first major project. Afterward, his career moves on fast. Without abandoning the discipline and technique he has acquired from the Bechers, he begins to take on large ideas and issues. It is his willingness to do so that animates this show.

In the 80s Struth continues to shoot architecture and

landscapes. Like his schoolmate Gursky, he takes up

color and begins to use photoshop to assemble from multiple viewpoints single

images of large locations and structures. But, unlike Gursky, who over the years

steadily creates more and more gigantic prints of larger and larger events,

(the Chicago Board of Trade, the Olympics) Struth’s big pictures seem uninterested in spectacle. Gursky

wins worldwide acclaim by moving farther and farther away from what he

photographs. Struth moves closer. His pictures, though still large and complex,

become more and more about the people present or implied within the frame. They radiate emotion that can be felt

by anyone.

These qualities

are best seen in the pictures the Met has collected from Struth’s three ongoing

series – roughly titled, “Museum,” “Paradise” and “Technology.”

Struth’s “Museum”

series comes from a simple idea. He photographs people looking at art and

history in museums all over the world. Strictly realistic, rendered in

sumptuous colors, these large, calm compositions at times resemble the Old

Master paintings that appear in many of the prints. Yet the unrehearsed modern tourist

crowds are always there too. Some museum-goers are reverent. Some are playing

with their iphones and thinking about their lunch. They bring a here-and-now immediacy to pictures meant

to last.

"Art Institute of Chicago,1990," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

"Museo Del Prado 7, 2005," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

The balance

between large ideas – the present and the past, the material and the spiritual,

for example – makes me wonder if Struth is aiming for the cusp between them? Or

do his museum pictures – like many of the old religion-based paintings depicted

within them –incline toward moral lessons? If so, the messages are hard to

recognize, extremely subtle. Yet the question continues to rise.

Asked about the

Museum series, Struth said “… the ineffable spills into the ordinary and the

spiritual aspirations of our ancestors intersect with the needs of the

present.” It’s clear that with these works Struth is gesturing toward something

beyond their quotidian content. In fact – like every artist -- he is imbuing

lifeless materials with human energy. Where does that energy come from?

We get to decide

for ourselves.

One thing I think

we know. In the Museum series the

goal of this energy is no longer the same as it is in the old paintings. Unlike

the paintings, the energy of the photographs is not directed at individual salvation.

We might think of its heaven as

salvation for all.

"Art Restorers at San Lorenzo Maggiore, Naples, Italy, 1988," Thomas Struth

I think this

becomes clear in Struth’s Paradise series. Photographed at ground level in

various rainforests in Japan, Australia and South America, all the images in

the series are called “paradise” and numbered. Only one, “Paradise 13, Yakushima, Japan 1999,” is included

in the show. Yet, from this

picture and others I have seen elsewhere, “paradise” seems a very odd title for

Struth to have chosen.

“Paradise 13,” for example, is shot deep inside a low, wet, dark forest strewn with fallen trees and moss-covered boulders. It is certainly no Eden. Struth is well-known as an ardent environmentalist, and it’s hard to imagine him resorting to cheap irony. Some of the other forest “interiors” in this series are tangles of dazzling green, flooded with transforming light. They are beautiful to look at and, as we know, vital to the health of our planet. But – come to think of it – real rainforests are always unrestrained riots of hungry competitive life. They are always difficult for humans. Struth is making a difficult point. Our human instinct is to transform them to meet our needs. But the Earth too needs salvation.

“Paradise 13,” for example, is shot deep inside a low, wet, dark forest strewn with fallen trees and moss-covered boulders. It is certainly no Eden. Struth is well-known as an ardent environmentalist, and it’s hard to imagine him resorting to cheap irony. Some of the other forest “interiors” in this series are tangles of dazzling green, flooded with transforming light. They are beautiful to look at and, as we know, vital to the health of our planet. But – come to think of it – real rainforests are always unrestrained riots of hungry competitive life. They are always difficult for humans. Struth is making a difficult point. Our human instinct is to transform them to meet our needs. But the Earth too needs salvation.

"Paradise 9," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

With the

“Technology” series, Struth asks: Does the human genius for technology threaten

our species? Does technology also offer hope? These too are ultimately

spiritual questions.

Struth’s “Hot Rolling Mill, Thysen Krupp

Steel, Duisburg, 2010,” takes us into the silent interior of a gigantic

industrial machine. By choosing an old German steel mill and associating it

with the name Krupp, Struth is deliberately evoking Hitler’s Third Reich and the

murderous weapons with which Germany came close to conquering the world. And the

picture itself -- a vast brutal wall of machinery in semi-darkness,

grime-encrusted, its khaki greens punctuated with the faded, reds and oranges of

catwalks and cables -- is indeed terrifying. Even worse, a thick chain is

bolted to the steel-plate floor in the only area lit by a window. It took bravery to make this picture. Struth

knows exactly what he is alluding to.

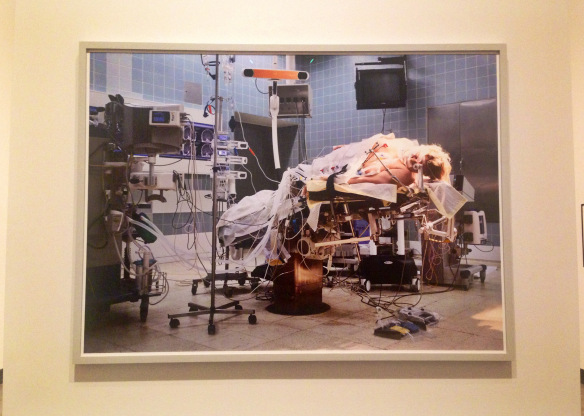

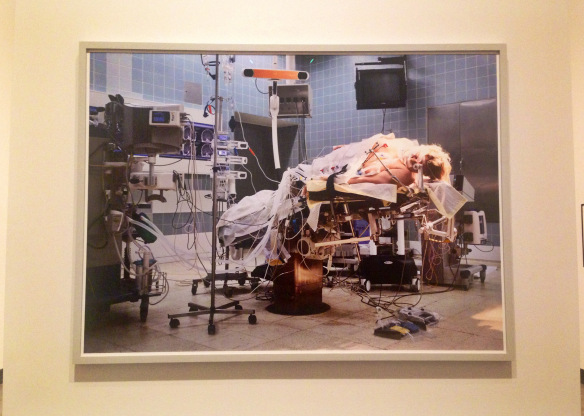

If “Hot Rolling

Mill” balances past and present, the most astonishing picture in the Technology

series presents itself literally as a fulcrum between present and future. Called “Figure 2, Charite, 2013,”

the picture shows a woman strapped to a medical gurney suspended in mid air. Looping

in from piled machines and monitors are dozens of wires, tubes and cables, all

of which attach to her body. At first, we recoil from the image. It seems to be

a Frankenstein-like experiment or perhaps some hideous torture. Then we notice

that the room is spotless, the light is clear and the woman is young and blonde

with beautiful skin. We are

confused. What are we looking at?

"Figure 2, Charite, 2013," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

"Figure 2, Charite, 2013," Thomas Struth, All rights reserved

It’s an operating

theater in Berlin, where this anaesthesized young woman is about to undergo surgery

to remove a brain tumor. With the woman’s full permission, Struth has

photographed the moment before the doctors and nurses enter to begin. We learn

in a caption that the woman survived and, two years, later is living

comfortably. Still, we wouldn’t know that if we hadn’t been told. Is Struth

intentionally frightening us with scary technology that is actually built and

used to save lives?

I don’t think so.

I think he is making full use of his freedom to challenge us. Some things that at first seem

repellent are beautiful. Struth’s mentors, the Bechers, photographed water

towers, silos and blast furnaces they judged beautiful – and safe to photograph

– in a defeated, divided Germany after a vicious war. Now, more than a half century later, Struth again finds

beauty in our still dangerous and increasingly complicated – but perhaps freer – world.

He makes big pictures for the world.

This review appears in The New York Photo Review