"Six" by Garry Winogrand at Pace McGill Gallery

Review by Tim Connor

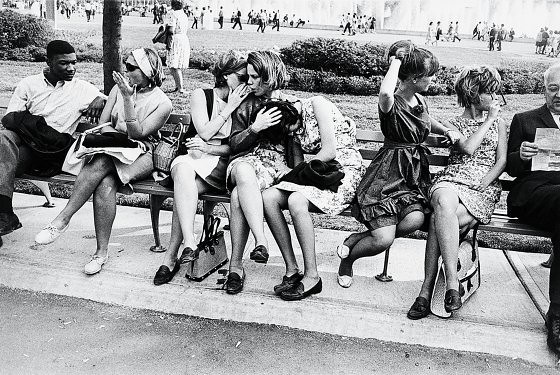

"El Morocco, New York City, 1969" by Garry Winogrand

"El Morocco, New York City, 1969" by Garry Winogrand

Pace McGill’s Garry Winogrand show, “Six,” might be thought

of as a kind of Cliff Notes for the full-dress Winogrand career retrospective running

this summer at the Met. At Pace

McGill, Winogrand’s well-known prints are large and crisp, and the crowds are

minimal, but how much, after all, can one learn from an outline?

Six images have been chosen for each of six categories -- Animals, Public Relations, Street, Women,

Central Park and Texas. Aside from

providing the title for the show, this 6 X 6 arrangement seems arbitrary and

unimaginative for work that openly – even ferociously -- eschews any kind of

shot-list mentality or after-the-fact categorization. But perhaps curation is beside the point. These are Winogrands, and Pace McGill wants to sell them (11”

x 14” print prices range from $5,000 to $65,000 – most are around $10,000).

To me, those prices don’t seem terribly high in this crazy

art market. After all, John Szarkowski, the great photographic critic and

kingmaker of the 1960s and 70s called Winogrand “…the central photographer of

his generation.” To be fair, this

was by no means a universal assessment at the time – nor is it today. But I

agree with Szarkowski, at least to the extent that Winogrand personified, more

than any of his contemporaries, a major attitudinal shift toward photography

that is still underway.

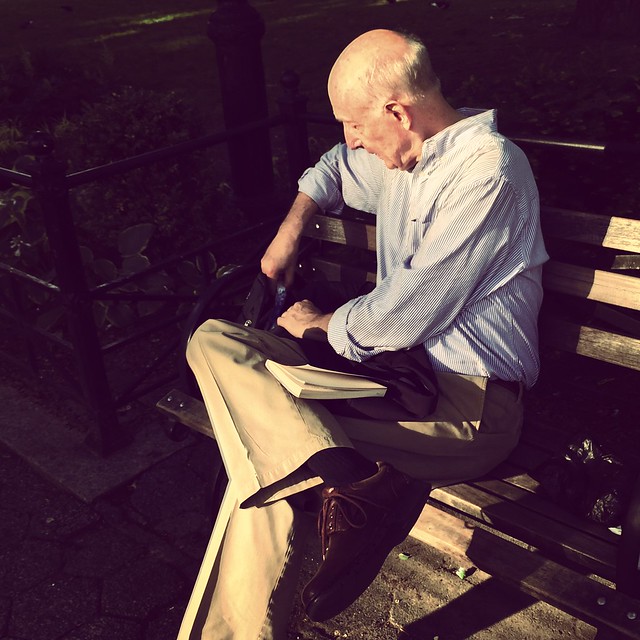

"New York City couple" by Garry Winogrand

"New York City couple" by Garry Winogrand

Winogrand’s career developed within and against the ideas of

an earlier generation of documentary and photojournalistic photographers who

believed the best of their work could accurately describe social and historical

truth and sometimes even change it. From Lewis Hines through W. Eugene Smith

(and continuing today) their theory goes: shine a bright, public light on

injustice, and you begin to attack and eliminate it. This theory was underpinned by optimism. We are all humans

with shared needs, problems and joys. And great photography proves it. This was the

message of “Family of Man,” the legendary exhibit curated by Edward Steichen,

mounted at MOMA in 1955, and then shown around the world.

In fact, Steichen selected two of Winogrand’s pictures for “Family of Man.” But, from the

beginning of his career, it was clear Winogrand was not that kind of

photographer. His passion was for the photograph itself -- not for what it

represented or could do. He was interested in human stories, but his stories

resisted moral judgments. They

could be ambiguous. It was as though he invited viewers to provide their own captions.

He went out in the morning to make great pictures but had no

idea what they’d be. By way of journalistic intention, he followed his

interests and obsessions. He went to places and events that he thought would

serve him, then, instead of “covering,” them, reacted to whatever caught his

attention. He felt no imperative to ask permission before or take moral

responsibility after taking a shot. His frames were always sliced from reality,

but they took no credit for being

reality. Szarkowski called Winogrand’s images “figments of the real world.” First

and last, they were pictures.

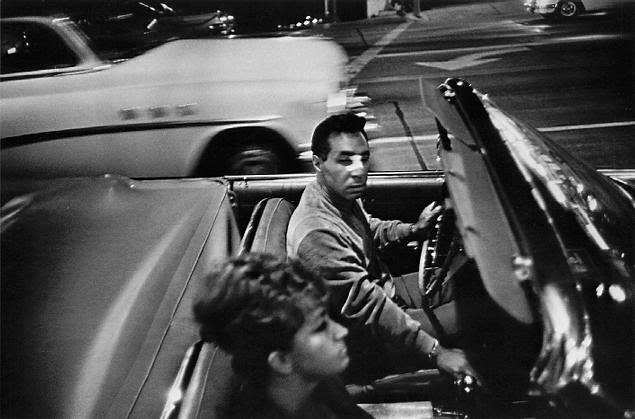

"Kennedy Space Center, Florida, 1969" by Garry Winogrand

"Kennedy Space Center, Florida, 1969" by Garry Winogrand

Winogrand is famous for saying, “I photograph to see what

something looks like photographed.” And he meant it. The idea was not to take

sides or advance an agenda but to discover what his camera had seen.

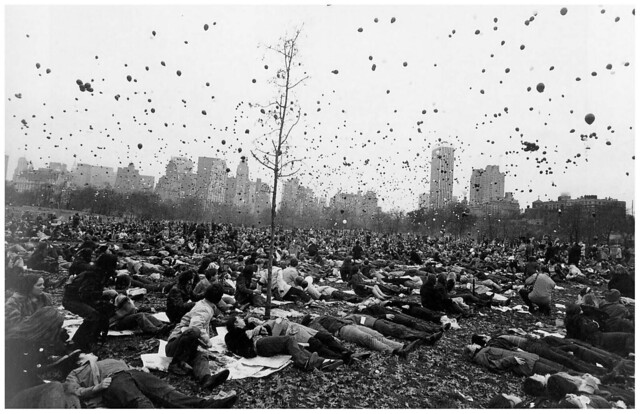

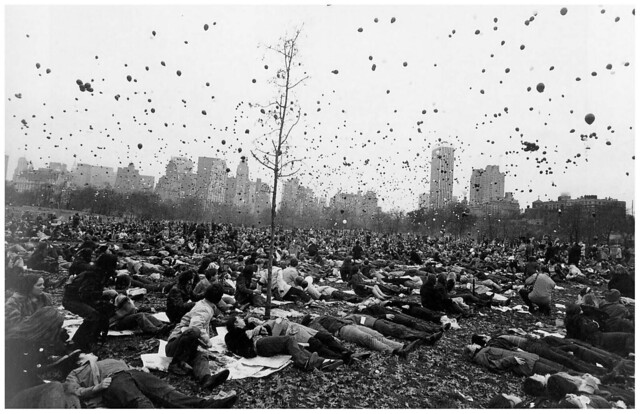

An example. Winogrand was against the Vietnam War. Yet his

best-known shot of the protests, “Peace Demonstration, Central Park, 1970,” displayed

in the exhibit’s Central Park section, shows a dark, gloomy day on Manhattan’s

Great Lawn. In the foreground is a spindly, leafless tree. Around it and

stretching to a horizon of East side buildings, a vast crowd of anti-war

demonstrators sits or lies huddled on the cold ground. The sky above the

protesters is thick with newly-released balloons that read as black in the black-and-white

print. Perhaps the real balloons were red, not black, against the darkening sky

that day. Or perhaps – let’s fantasize -- they were bombs falling. We really don’t

know from the picture, just as we don’t know why the crowd is so passive about

the spectacle

"Peace demonstration, Central Park, 1970" by Garry Winogrand

"Peace demonstration, Central Park, 1970" by Garry Winogrand

As viewers 44

years later, the scene frankly looks sinister, almost apocalyptic. It goes

firmly against our received idea of what an anti-Vietnam War demonstration is

supposed to look like. Winogrand’s “historical” pictures are often different in

that way.

He was in fact a kind of anti-historian. In a 1971 picture,

again from the show’s “Central Park” section – and again in cold but snowless

weather -- a classic “straight” family of tourists (short-haired father in double-breasted

trench coat; wife with hair tied in a scarf; two boys wearing cheap street-bought

cowboy hats) stand gazing over five long-haired hippies (hatless, moustached,

shades) lounging on the frozen grass. What is the family looking at? Perhaps we're at the outskirts of another

demonstration. Why do the hippies so studiously ignore the family? Why do they –

the cool insiders -- appear so rattled? Could it be that, “Somethin’s happenin here but

you don’t know what it is…”? Could

it be that Mr. and Mrs Jones and

the kids don’t care?

"Central Park, 1971" by Garry Winogrand

Winogrand shot without thinking too much – more frames, more

rolls, than any of his contemporaries.

Then he edited , selecting

what he considered to be the best pictures, not the ones he thought would

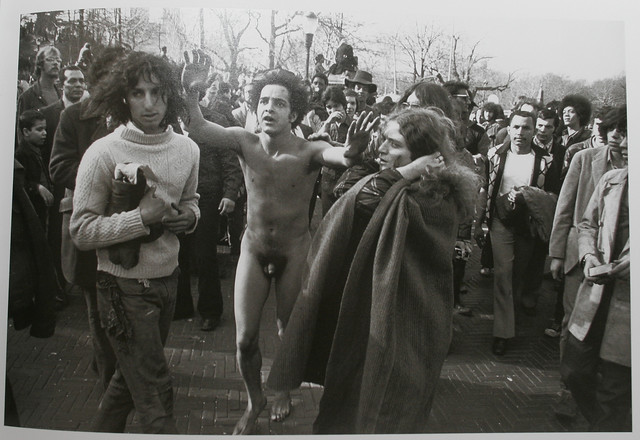

please. For instance, the disturbing “Easter Sunday, Central Park, 1971” shows

three young people obviously tripping, surrounded by a curious, not necessarily sympathetic crowd.

One man is completely naked. His

hands are raised, as though he’s invoking the heavens. The other two, a man and

a woman, look agitated. There is no caption describing this scene, but the paranoid-ecstatic, staring eyes of all three trippers -- as though

they are seeing god and the devil at the same time – tell the tale.

“Easter Sunday, Central Park, 1971” by Garry Winogrand

“Easter Sunday, Central Park, 1971” by Garry Winogrand

Yes, but why

are we looking at this picture? It’s not an anti-drug ad. It’s also not, in any coherent historical

sense, about the event that surrounds it. In the end it’s just a fascinating “figment” -- at a time when fervently

confused religious seekers in New York City might find Easter Sunday an

auspicious time to drop acid and attend demonstrations. I guess that’s

history too.

Supposedly, Garry Winogrand fell apart as a photographer

after he moved to Los Angeles late in life. He continued to shoot but stopped

editing, finally even stopped processing his film. After his death, no less a personage than his old friend and

mentor Szarkowski examined the massive take he had left behind – reportedly as

many as 300,000 unedited images – and pronounced them unremarkable. Since then,

experts at the Met have taken another look and are including some of the unseen

shots in their retrospective.

What’s the verdict? Did he lose it? Was he great till the

end? I hope so, but it doesn't really matter. Garry Winogrand’s open-minded, follow-your-instincts, shoot-what’s-there aesthetic

recorded the American 60s and 70s like no one else. His example has become the working

mode of many thousands of today's shooters – both pros and amateurs -- worldwide. I

think it’s safe to say that, working the way he did, these photographers intuitively understand Winogrand’s enigmatic dictum: “Nothing is more

mysterious than a fact clearly stated.”

This review also appears in the current issue of New York Photo Review.

To read more of my reviews of photography, other visual arts, books and movies, click here.