"Humans of New York," Brandon Stanton, All rights reserved

Just a week after its publication, Brandon Stanton’s photo book, Humans of New York, jumped to number one on the Times best-seller list. To make the book, Stanton walked all five boroughs (but mostly Manhattan) with his camera, approached people he found interesting, started up conversations and asked to take their pictures. Not only did the people agree, they opened up for surprisingly unguarded portraits; many also gave Stanton intimate quotes for attribution, as though he was a trusted friend.

Does this sound like a classic New York artist’s fairy tale?

Well, it is. And here comes its

modern twist: Stanton was not discovered by a John Szarkowski-style prince of

taste but by millions of viewers on the internet. To become the people’s choice

Stanton began showing his pictures on photoblogs and social media in 2010. The last time I visited his “Humans of

New York” (HONY) page on Facebook, it had been “liked” by 1,772,196 visitors,

and each of the page’s hundreds of pictures had themselves inspired hundreds or

thousands of comments.

These are astonishing numbers. What makes the pictures so popular? Certainly, Stanton’s well-made color portraits are uniformly pleasing. Straightforward and unfussy, they fill out a New York City “gorgeous mosaic” of demographic diversity with an eye for individual style and a flair for tripping the shutter at the perfect moment. Perhaps Stanton’s real gift, in fact, is his ability to create that moment – to persuade strangers to feel good about him, his project and ultimately themselves.

In addition, Stanton is a sympathetic interviewer. As he shoots, he asks big questions, such as “What is your biggest struggle?” The answers range from ironic (often very funny) quips to true attempts at self-revelation. Later, Stanton combines his subjects’ edited answers with their pictures to create funny, swoony or sad little stories.

"Humans of New York," Brandon Stanton, All rights reservedOn a rainy street, for instance, he asks a mysteriously smiling young woman, “What was the happiest moment of your life?” The woman replies: “There are two. The day my baby was born, and last night.” Responding to another question, an elegant old woman in a fur hat looks proudly at the lens and says, “When my husband was dying, I said, ‘Moe, how am I supposed to live without you?’ He told me, ’Take the love and spread it around.’ “

I’m told this collection moves many viewers to tears. I’m guessing most of these are what people call ‘happy’ tears. Most viewers – like most of the people photographed -- seem helpless against Stanton’s optimistic charm and genuine affection. In this book, buoyed up by his eager energy, dancers dance, lovers kiss and old grumps laugh aloud. For a moment this friendly young man seems able to create an experience of deeply-felt community.

His style, it seems to me, embodies our cultural moment’s ideal template for photographic portraiture. Everything is in the open. No pictures are taken without full permission. Editing and usage rights are theoretically collaborative. Recorded words are reliably accurate and respect the true context in which they were spoken. The final photographs represent a synergy of shooter and subject. Posted to the internet, they become a kind of collective.

I’m guessing that most of Stanton’s subjects felt they were posing under just such an unwritten moral contract (legal realities may be different). No doubt they felt good about it. Stanton’s wide-open, democratic style is the flip side, after all, of the rampant insecurity and paranoia that curls more and more insistently through our high-tech society – and often surfaces around photography. “That man with the camera,” we fret. “Is he pointing it at us? Is he the government, a stalker, a pervert? Is he looking at the kids?” Such fears may be extreme, but they’re not contemptible. There’s a reason for them to exist.

Nevertheless, as a critic, I’m concerned about this trend. If photographers and their intentions are

forced to endure such fear-driven vetting, will only feel-good,

we-did-this-together projects like Stanton’s be able to thrive? I say this as a

sincere fan of “Humans of New York.”

I admire its steady, non-judgmental acceptance of its subjects’ offerings. But

I worry about photographers who use very different methods and mine very

different veins.

"Lower East Side Children," Helen Levitt, All rights reserved

Take Helen Levitt, who died a few years ago. Regularly

described as “shy and retiring,” she walked the streets of Harlem and the Lower

East Side anonymously for 60 years, photographing and filming people -- most

often, children – using cameras fitted with a right angle viewer, called a

‘Winkelsucher,’ that allowed Levitt to stand sideways to her actual subjects.

In other words, she snuck shots in pursuit of what legendary author James Agee

called “…a fleeting and half-secret world… most abundant in lyrical qualities.”

"Girl at Window," Helen Levitt, All rights reserved

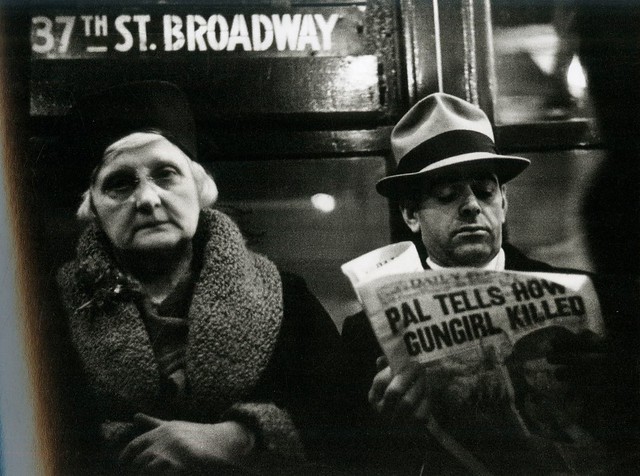

Levitt’s colleague and friend Walker Evans did something

similar in his famous subway series, “Many Are Called.” With Levitt often sitting

by his side, Evans rode the New York trains for weeks making exposures with a

tiny camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat. Riders among the daily mass migration rarely noticed, but there

was nothing dishonest about the pictures. Looked at now, Evan’s pictures, like

Levitt’s, are a triumph of humanist affirmation.

"Many Are Called," Walker Evans, All rights reserved

Does “Humans…” give us a truer look at New Yorkers than the

street portraits of the past or today's by other photographers?

I’d say it gives us another kind of look – a familiar modern look,

balanced on the tightrope between disguise and revelation. Call it a social

media look. My recommendation is:

If you can’t afford the book, at least check out the website

(humansofnewyork.com). It may be the first big mainstream collection that takes

for granted the facebook selves – at once pleading and performative – that we willingly

reveal to our linked-up world.

This review also appears in The New York Photo Review