Saturday, December 21, 2013

My photo published in 'Exposure 2011'

"Due Date," Tim Connor, All rights reserved

A big sleek hardcover book arrived for me in the mail yesterday. It's the photo choices for "Exposure 2011," a contest sponsored by 'See.Me' (then known as 'Artists Wanted'). My entry (shown above) is one of perhaps a thousand in this beautiful 320-page tome -- a neat job, printed entirely on lustrous black stock.

I guess See.Me didn't try to publicize it because it's almost three years late (contest was 2011; copyright is 2012; in a few days it will be 2014). But, after all, they did send it, just in time for Christmas, presumably to all the photographers, and I appreciate that.

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

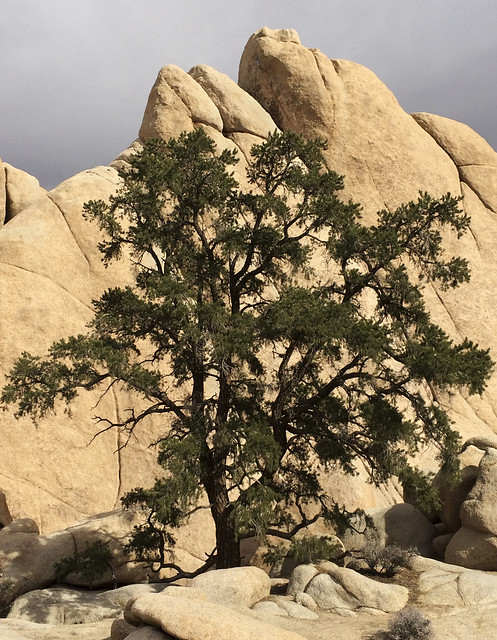

High desert

Tuesday, December 3, 2013

Persistent mystery

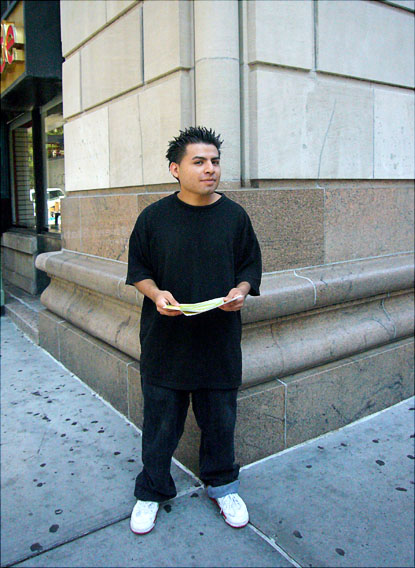

"Handout man, Manhattan," Tim Connor, All rights reserved

I'm not much of a numbers' man, but occasionally I like to look at Flickr's stat summaries for photos I've posted. Some surprise me. The picture above, for instance, has been viewed 26,016 times.

That's a lot of views.

I don't get it. I understand how this one, received 12,530 views:

"Drunk blonde with Siamese twins, the Mermaid Parade," Tim Connor, All rights reserved

But the kid handing out Emma's Dilemma coupons on Park Ave. South I don't get. I shot this picture in 2007. It ended up in a show called " 'New' New Yorkers" at Judson Church in 2009. I stopped trying to photograph street handout people soon afterward because most of my potential subjects declined -- very nervously -- to be shot. They were afraid I had something to do with Immigration.

So how does this picture draw 26,016 people to come to my modest little blog page? What's your theory?

My submissions to " 'New' New Yorkers" are here.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Brandon Stanton's "Humans of New York"

"Humans of New York," Brandon Stanton, All rights reserved

Just a week after its publication, Brandon Stanton’s photo book, Humans of New York, jumped to number one on the Times best-seller list. To make the book, Stanton walked all five boroughs (but mostly Manhattan) with his camera, approached people he found interesting, started up conversations and asked to take their pictures. Not only did the people agree, they opened up for surprisingly unguarded portraits; many also gave Stanton intimate quotes for attribution, as though he was a trusted friend.

Does this sound like a classic New York artist’s fairy tale?

Well, it is. And here comes its

modern twist: Stanton was not discovered by a John Szarkowski-style prince of

taste but by millions of viewers on the internet. To become the people’s choice

Stanton began showing his pictures on photoblogs and social media in 2010. The last time I visited his “Humans of

New York” (HONY) page on Facebook, it had been “liked” by 1,772,196 visitors,

and each of the page’s hundreds of pictures had themselves inspired hundreds or

thousands of comments.

These are astonishing numbers. What makes the pictures so popular? Certainly, Stanton’s well-made color portraits are uniformly pleasing. Straightforward and unfussy, they fill out a New York City “gorgeous mosaic” of demographic diversity with an eye for individual style and a flair for tripping the shutter at the perfect moment. Perhaps Stanton’s real gift, in fact, is his ability to create that moment – to persuade strangers to feel good about him, his project and ultimately themselves.

In addition, Stanton is a sympathetic interviewer. As he shoots, he asks big questions, such as “What is your biggest struggle?” The answers range from ironic (often very funny) quips to true attempts at self-revelation. Later, Stanton combines his subjects’ edited answers with their pictures to create funny, swoony or sad little stories.

"Humans of New York," Brandon Stanton, All rights reservedOn a rainy street, for instance, he asks a mysteriously smiling young woman, “What was the happiest moment of your life?” The woman replies: “There are two. The day my baby was born, and last night.” Responding to another question, an elegant old woman in a fur hat looks proudly at the lens and says, “When my husband was dying, I said, ‘Moe, how am I supposed to live without you?’ He told me, ’Take the love and spread it around.’ “

I’m told this collection moves many viewers to tears. I’m guessing most of these are what people call ‘happy’ tears. Most viewers – like most of the people photographed -- seem helpless against Stanton’s optimistic charm and genuine affection. In this book, buoyed up by his eager energy, dancers dance, lovers kiss and old grumps laugh aloud. For a moment this friendly young man seems able to create an experience of deeply-felt community.

His style, it seems to me, embodies our cultural moment’s ideal template for photographic portraiture. Everything is in the open. No pictures are taken without full permission. Editing and usage rights are theoretically collaborative. Recorded words are reliably accurate and respect the true context in which they were spoken. The final photographs represent a synergy of shooter and subject. Posted to the internet, they become a kind of collective.

I’m guessing that most of Stanton’s subjects felt they were posing under just such an unwritten moral contract (legal realities may be different). No doubt they felt good about it. Stanton’s wide-open, democratic style is the flip side, after all, of the rampant insecurity and paranoia that curls more and more insistently through our high-tech society – and often surfaces around photography. “That man with the camera,” we fret. “Is he pointing it at us? Is he the government, a stalker, a pervert? Is he looking at the kids?” Such fears may be extreme, but they’re not contemptible. There’s a reason for them to exist.

Nevertheless, as a critic, I’m concerned about this trend. If photographers and their intentions are

forced to endure such fear-driven vetting, will only feel-good,

we-did-this-together projects like Stanton’s be able to thrive? I say this as a

sincere fan of “Humans of New York.”

I admire its steady, non-judgmental acceptance of its subjects’ offerings. But

I worry about photographers who use very different methods and mine very

different veins.

"Lower East Side Children," Helen Levitt, All rights reserved

Take Helen Levitt, who died a few years ago. Regularly

described as “shy and retiring,” she walked the streets of Harlem and the Lower

East Side anonymously for 60 years, photographing and filming people -- most

often, children – using cameras fitted with a right angle viewer, called a

‘Winkelsucher,’ that allowed Levitt to stand sideways to her actual subjects.

In other words, she snuck shots in pursuit of what legendary author James Agee

called “…a fleeting and half-secret world… most abundant in lyrical qualities.”

"Girl at Window," Helen Levitt, All rights reserved

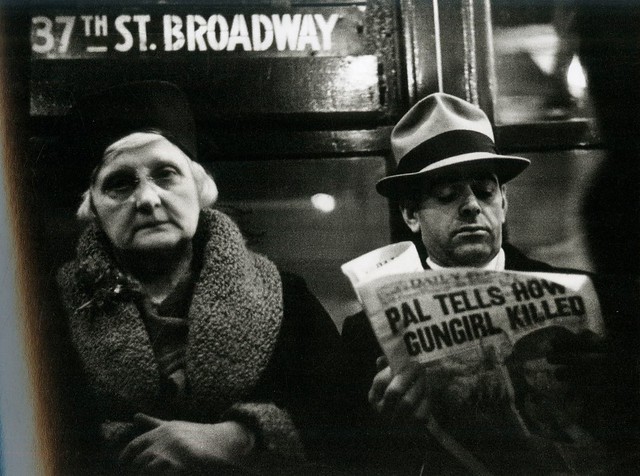

Levitt’s colleague and friend Walker Evans did something

similar in his famous subway series, “Many Are Called.” With Levitt often sitting

by his side, Evans rode the New York trains for weeks making exposures with a

tiny camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat. Riders among the daily mass migration rarely noticed, but there

was nothing dishonest about the pictures. Looked at now, Evan’s pictures, like

Levitt’s, are a triumph of humanist affirmation.

"Many Are Called," Walker Evans, All rights reserved

Does “Humans…” give us a truer look at New Yorkers than the

street portraits of the past or today's by other photographers?

I’d say it gives us another kind of look – a familiar modern look,

balanced on the tightrope between disguise and revelation. Call it a social

media look. My recommendation is:

If you can’t afford the book, at least check out the website

(humansofnewyork.com). It may be the first big mainstream collection that takes

for granted the facebook selves – at once pleading and performative – that we willingly

reveal to our linked-up world.

This review also appears in The New York Photo Review

Thursday, November 14, 2013

Taking the long view

Here is some gorgeous rhetoric by author Lee Billings from his book, Five Billion Years of Solitude, reviewed in this week's New York Times Book Review. This passage was chosen by Dennis Overbye, the reviewer.

"A planet becomes a vast machine, or an organism, pursuing some impenetrable purpose through its continental collisions and volcanic outpourings. A man becomes a protein-sheathed splash of ocean raised from rock to breathe the sky, an eater of sun whose atoms were forged in an anvil of stars."

"A planet becomes a vast machine, or an organism, pursuing some impenetrable purpose through its continental collisions and volcanic outpourings. A man becomes a protein-sheathed splash of ocean raised from rock to breathe the sky, an eater of sun whose atoms were forged in an anvil of stars."

Friday, November 8, 2013

Spastic plastic fantastic

Saturday, November 2, 2013

Apocalypse in miniature: Lori Nix's 'More from The City'

"Subway," Lori Nix, All rights reserved

While never completely out of fashion, apocalyptic fantasy art was once the realm of disillusioned outsiders. No longer. Baying forth directly from the deep pockets of corporate high tech, today’s sleek, dystopian movies, TV, video games and other visual media now dominate our imaginative culture. At the same time apocalypse-themed fiction and nonfiction books and journalism drive much of our intellectual discourse. No civilization has ever been more thrilled by its own demise.

Photographer Lori Nix’s end-of-the-world show, “The City,” at Clampart covers this familiar territory but not without staking out its own brand of modesty and wit. A self-proclaimed “danger and disaster” artist, Nix admits to being “fascinated, maybe even a little obsessed, with the idea of the apocalypse.” Her show imagines a New York City in which all humans have been suddenly terminated, leaving behind only their objects and buildings. This “post-human” metropolis is depicted in large color prints of iconic public spaces — a library, a shoe store, a Chinese take-out restaurant, etc.

The verisimilitude of the little worlds is remarkable. But Nix’s miniature power tools are, after all, not CGI and her old-school archival color printing is not Photoshop. Her interiors are sometimes flawed. Not often, and not by much, but enough so a close viewer will notice. For instance, the show’s advertising shot, a cunningly realistic B subway train, forever stalled and filling up with sand at the Brooklyn end of the Manhattan Bridge, looks across a sand-locked East River to a rudimentary stage-set drawing of the Manhattan skyline. Why not make the skyline look as real as everything else?

"Chinese Take-Out," Lori Nix, All rights reserved

I’m guessing Nix wants her pictures to inspire awe and unease at a distance and then––as the viewer takes a closer, more leisurely view––provide pleasure and a few chuckles. Her “Chinese Take-Out” picture, for example, brilliantly conjures the formulaic elements of such places – basic store front décor, a picture of ancient temple from the old country, standard OSHA “First aid for choking” poster and two sets of what-you-see-you-get food photos of General Tso’s Chicken, Vegetable Lo Mein and other dishes, identified in Mandarin and English. The fabricators have taken great pains to “distress” the interior with dirt and grime and to strew around red-stamp-labeled take-out containers and authentic-looking pages from a tiny New York Times. But when Nix places a blue delivery scooter right at the front of the room, it’s impossible to miss that it’s a child’s toy. And, look, what’s that sneaking through the open kitchen door? It’s a stuffed red fox. Should I be surprised when a quick Google search reveals that – according to Chinese tradition — the fox is a signal from the spirits of the dead?

"Casino," Lori Nix, All rights reserved

I don’t think so. After scheming and tinkering for over half a year on these pint-sized replicas, I imagine very little – if anything – has been missed. What’s more, the playfulness turns up in the other pictures, too. For instance, in “Space Center,” imagined as a once proud, now desolate museum of human flight, two hawks are busily nesting in what’s left of a Mars Rover. In “Casino,” the ceiling is torn open like a tomb to reveal cheesy replicas of dynastic Egyptian guardian statues standing against walls covered with hieroglyphics. The floor is filled with rusting slot machines that bear names like “Strike It Rich.” One of them is called “Doomsday.”

I’m glad that Lori Nix is making pictures of disaster we can really look at. With its low-tech craft and slow-dawning gags her work feels personal – to her and to us. We are invited into a very still, and sad — and undeniably ridiculous — made-up world. It occurs to me this may be a better place to contemplate human folly than shoulder to shoulder with a movie star as he mows down zombies.

Originally published in The New York Photo Review

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Here, kitty kitty...

Thursday, October 10, 2013

Saturday, October 5, 2013

Friday, October 4, 2013

Phone among phones

"Two street phones" by Tim Connor, All rights reserved

Taken with my new iphone 5S. I didn't buy this phone/camera to shoot Gary Winnogrand-style street snaps, but that's about all I've done so far. The FS camera is well-suited to nervy spontaneous shooting, though it's awkward as hell (I keep shooting pictures of my big pink figures). For one thing the Fs's fully automatic white balance and metering systems handle mixed NYC color and light brilliantly so far. I'm pleased with the quality.

But, way more important, shooting with a phone seems to excuse my voyeuristic perfidy! I' m just a guy with a phone! No one is worried about a guy with a phone. Look, everybody is walking around with them-- handling them, playing with them, peering at them, listening and talking to them, tapping and swiping at them. What could be more harmless?

"Two girls and a small boy, Washington Square" by Tim Connor, All rights reserved

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Young Davey

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Thursday, September 5, 2013

A long time ago

Big River, Mendocino, CA, Tim Connor, All rights reserved

On and off in the pre-digital 70s I experimented with infrared film. This picture was processed in Photoshop from a scan of one of those old negs. I have never worked with infrared outside the darkroom so this is all improv. If any of you know of any online examples of infrared via Photoshop, I'd love to look at them. Please send me a note.

P.S. I've also dug up negs that I shot on Ilford XP1 400 ASA film and developed god knows how (I don't remember). The negs have a brownish-orange cast and display infrared contrast and reverse densities.

For this project (both kinds of film) I have in mind to get color into the mix somehow. Don't have a clue how to go about that (still a fumbling beginner in PS). Any suggestions welcome.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Martin Parr -- "Life's a Beach." A review

"Knotte, Belgium," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

First, an admission. Before I looked at his show, “Life’s a Beach,” at Aperture Gallery, I had convinced myself that Martin Parr’s hyper-bright, in-your-face ironies were mostly an exercise in hype -- a sort of art brand on the make. But I left the show thoroughly charmed.

How did that happen? Before this, I had only seen Parr’s work sized small, online or

in magazines, and had gotten the idea his pictures were supposed to be jokes. In fact, I enjoy jokes, but Parr’s images

had seemed to me detached and over-calculated, like a comedian’s punch lines

with choreographed pauses for laughter. Looking in the context of this show’s large

prints, I saw that his work is much more complicated than that.

Is Parr’s work funny? Yes, often. Does he shoot as an

outsider? Yes, of course. Parr could

never manage his pictures if he was also participating in the dramas swirling

around in the frame. On the other hand, he could never get the shots at all if

he didn’t have a participant’s instinctive knowledge of what’s going on.

"Art," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

I imagine Parr as a participant-observer, a sort of photo primatologist

among his peers. Put simply, he

understands that – released from workaday

discipline by holidays or special events – ordinary people behave like the complicated

primates we actually are. We gossip, flirt, eat, play games, make jokes, dress

up in uniforms and costumes, dance, drink, bask, show off, analyze each other’s

status, display awful – if exuberant – taste and so on. In these settings Parr seems to have

found his gift in another primate ritual.

He takes pictures.

"Art," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

In Parr’s career he has showed us ourselves abundantly -- through

50 books and over 80 major exhibitions of photographs, four movies, numerous TV

documentaries, membership in Magnum, a co-written scholarly history of photo

albums, an extensive post card collection and more.

The man loves pictures.

"Think of England," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

In “Life’s a Beach” Parr has for the first time assembled

his best work from a 30-year obsession with photographing beaches around the

world. The prints push-pinned to Aperture’s walls include work from Argentina, Brazil, China, Spain,

Latvia, Japan, the United States, Mexico, Thailand and the United Kingdom. For

Parr, beaches are “…that rare public space in which general absurdities and

local quirks seamlessly fuse together.”

Some of the images are indeed evocative of every culture. Parr’s

iconic 1997 shot of a sunbathing older woman, for instance, delivers a maximal

satiric jolt by cropping out everything but her glistening, sunburned face and

arms. Even in the savage heat of the mid-day beach, the woman wears all her gold

jewelry. Her thin, freshly-lipsticked

mouth is pursed grimly, and -- where her eyes ought to be -- surreal bright

blue protective eye-cups seem to pop with otherworldly rage.

"Sunbathing lady," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

"Sunbathing lady," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

Who is this terrifying woman? Why is she so angry? Parr

leaves it to our imagination. Every culture has agreed-upon types to refer to. The

picture was taken in Benidorm, Spain

-- perhaps the woman is a fierce duenna, strictly chaperoning a family’s sulky adolescent

daughter. Maybe the correct title should be dowager –she’s an updated British version of Wilde’s

Lady Bracknell. Other tribes will

assign their own special roles.

"American speedo," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

"Rio beach boy," Martin Parr, All rights reserved

Parr’s pictures also nail specific cultures. A garish stars-and-stripes-themed

speedo droops off the sagging ass of a middle-aged man from Miami; a godlike,

gleaming black beach boy from Rio sizes us up through designer sunglasses; in

places like New Brighton and Eastbourne, beachgoers in robes and sensible shoes sit in folding chairs

and read headlines like “I Want to Hang Them” or “Fergie’s Final Boob;” in

Miyazaki, Japan, hundreds of revelers frolic happily in artificial surf under fluorescent

lights in a place called Ocean Dome.

Other pictures move across the sticky divide between

cultures. For example, on a beach in Goa, India, a young Western couple encamped

with flip flops and towels are disconcerted by a large white sacred cow, which gazes

at them mournfully as two fully dressed Indian men stride purposefully by.

It’s interesting that so few of these cross-cultural shots

cause the viewer any real discomfort. The only picture in the show that is at

all disturbing depicts a big beefy Western man lounging under a palm tree, simultaneously

getting a manicure and a pedicure from two tiny Balinese. The picture has a slightly seedy, obscene

feeling. But it’s hardly gut-wrenching.

I wonder -- not

for the first time – why Parr chooses to take the viewer to the point of

laughing out loud but never to the verge of outrage. And then I wonder, why am I even thinking about chastising

Parr for not making me angry? By the

end of the show I decide to appreciate his gentleness. As a shooter, he has the

chutzpah to walk up to strangers and fire off his ring-flash from closeup

range, but the resulting photographs – though bold and arresting -- are the opposite of harsh. In fact, I’d

call them deeply sympathetic, even rather

fond.

Parr is a skilled satirist, but from the evidence, not an

angry one. To my eye he seems at

least as interested in entertaining viewers as in changing their mind. Enjoy

him.

More reviews on this blog

More reviews on this blog

Friday, April 5, 2013

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Spring fever

Saturday, March 23, 2013

A different kind of history

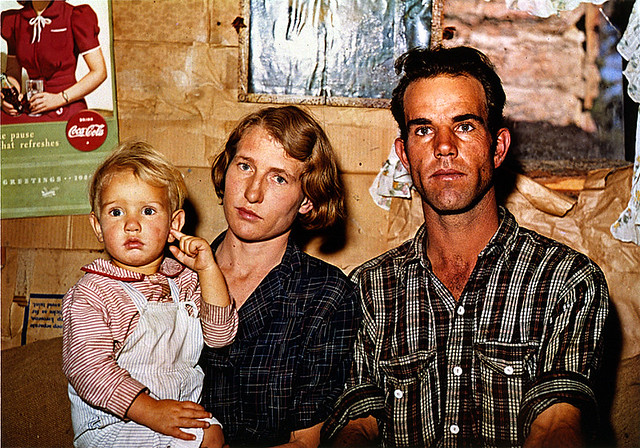

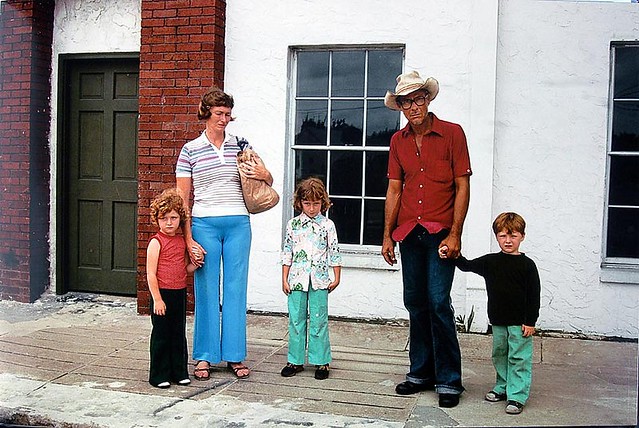

Russell Lee, Jack Whinery, Homesteader and Family, Pietown, New Mexico, September, 1940

The 31 photographers included in "Everyday America, Photographs from the Berman Collection," at Kasher Gallery cover more than 75 years of

America’s story, but the people

and events scholars might deem the proper content of our national history are

not here. Instead the photographers present a sort of hodgepodge history of

images anyone might have noticed -- and possibly thought unremarkable. Here’s

a partial list of subjects: houses, shopkeepers, vehicles, lovers, amusement parks,

suburbs, couples, orchards, graves, dancers, motels, kids, train trestles, shoppers,

barber shops (I could go on and on).

This is a different kind of history, and I

don’t mean to make fun of it. On the contrary, arranging the pictures outside a

historical context seems in keeping with their essential idea – they were shot in history, not about it. By not

attaching the photographers’ names and picture titles alongside the works, the curators

go further toward isolating the images in their own discrete moments (catalogs are readily available). I found

the disorientaion refreshing. The experience became just me and the images – like peering

though a viewfinder moving randomly through time.

And the pictures are superb. Roughly grouped under the rubric of

“documentary,” the photographers avoid sentimentality and (except for one

mocking photo by Martin Parr) post-modern irony. Their tool of choice is most

often a large, unwieldly 4x5 or 8x10 view camera, which requires fixed

intentions and emphasizes clarity and specificity.

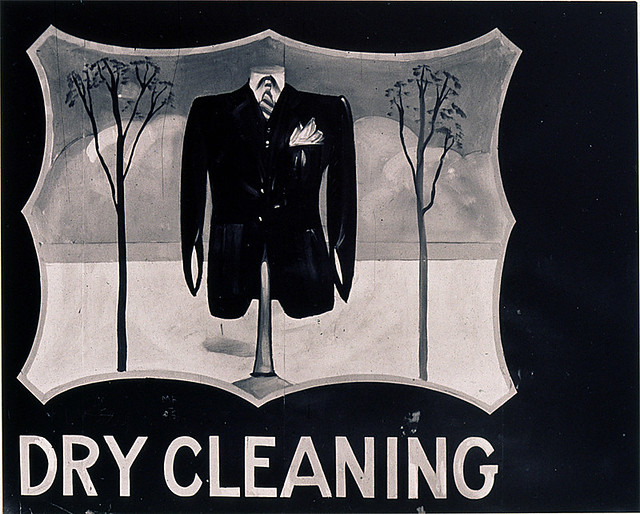

Arguably, almost all the styles in this show can

be understood as versions of Walker Evans’ style. And, indeed, Evans -- with

the largest number and often the best pictures in the show -- is the star here.

We see, for example, his fascination with the art and language of commercial

displays – he called them “the pitch direct” –echoed in pictures by Aaron

Siskind and John Vachon and expanded to church signs and scribbled graffiti by

Dorothea Lange and Helen Levitt.

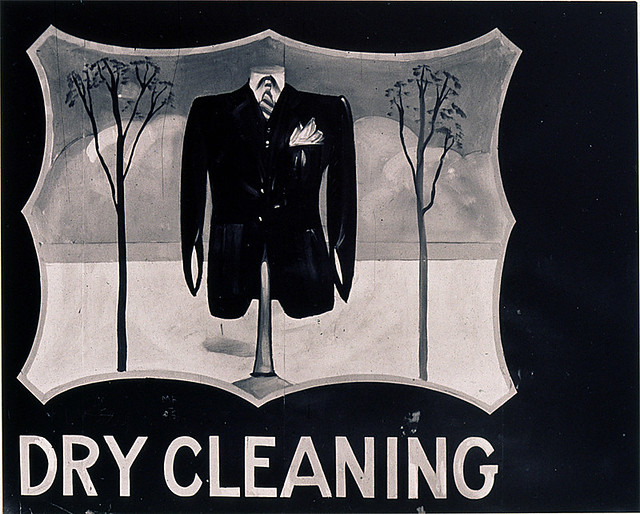

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935”

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935”

Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935”

Walker Evans, “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1935” Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

Walker Evans, “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936”

It was Evans who first understood that the

written word in public is important socially and aesthetically. His homage to skilled and graceful

sign-painting in “Outdoor Advertising Sign

(Dry Cleaning) near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1935” and minimalist white-paint-on-black board in “Shoeshine Shine in a

Southern Town, 1936,” for instance, show us that – long before MBAs discovered them

-- brands were, for good or evil, indelible.

Or they can be chaotic, as Robert Frank shows in

his 35mm. New York street shot, “Untitled (Poultry Store Front), 1950s. ” In

the shot a messy script, daubed on a sign above a trash-filled sidewalk, maniacally

proclaims “1-pound giblets for $3” over and over and over. This is Frank working characteristically

against the grain. He is no doubt well aware that the signs’ thumbed-nose to

craftsmanship represents a social change. What has happened to Evans’ folk artist/sign painter? Is he drunk? Or has be been replaced by a

machine?

The transformation of the show’s themes over

time is one of its great pleasures. For instance, John Humble, a west coast photographer

has photographed the streets and buildings of Los Angeles in large-format color

since the 1970s. His color shot of a low-slung fast-food restaurant, the show’s

“12511

Venice Blvd, Mar Vista (Canton Kitchen), 1997” at first seems garish with multiple signs and neon windows. But we soon understand that Humble’s picture is in its way as modest

and precise as one of Evans.

John Humble, 12511 Venice Blvd., Mar Vista (Canton Kitchen), January 8, 1997

John Humble, 12511 Venice Blvd., Mar Vista (Canton Kitchen), January 8, 1997

What’s different in this picture (aside from

the color) is the rest of the world. The Canton Kitchen itself, a place about

the size of a Manhattan studio apartment, is crouched in the shadow of an

appliance parts warehouse under an illuminated billboard and, on the other side,

pushed up against a nondescript parking lot. Given this, and the fact that no

one walks in L.A., it’s hardly surprising that four signs are needed -- one of

them towering above the tiny building (Chinese FOOD to GO). We’re not in 1930s Connecticut

anymore.

Numerous examples from the show make clear that

Evans was drawn to deserted, closed and boarded-up buildings, a theme repeated here

by William Christenberry, Jack Delano, David Husom and Mitch Epstein, among

others. But where Christenberry’s freshly-painted white church, in Hale County,

Alabama in the 1970s, for example, exudes hope despite the boards nailed over

its windows, Epstein’s bricked-up factories in Holyoke, Massachusetts in 2000

emanate despair. Buildings have a spirit, just like living creatures.

It was Evans’ great gift to infuse inanimate

objects with a tender life most photographers grant only to other human beings.

But, perhaps as a corollary of this, he seemed reluctant throughout his career

to make intimate portraits, preferring to pose people in the midst of larger

scenes, if at all. (An exception – perhaps a telling one – is his New York City series of subway portraits, shot in secret, spy-camera-style.)

Mitch Epstein, Newton Street Row Houses, (Brownstone Building), Holyoke, Massachusetts, 2000

Mitch Epstein, Newton Street Row Houses, (Brownstone Building), Holyoke, Massachusetts, 2000

Could an unconscious aping of Evans’

people-shyness by curators or collector explain why so few portraits are in

this show? It’s a real surprise, given the size of the space, that all the significant

people pictures can be grouped in one corner. Clearly, this is not because they’re unconvincing or weak.

On the contrary, this section of the show may be its liveliest.

This is in spite of the fact that many of the

portraits in “Everyday America” are not “everyday” at all. They are classic

black and white prints by Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White and other

Depression-era shooters of refugee families and young working men fleeing the

dust-bowl. These dramatic pictures

are interesting, but there’s something musty and old-fashioned about them. They were widely published at the time and are now so well-known as a genre it’s

hard to really see them clearly. But then comes an early color shot by FSA

photographer Russell Lee to pierce through the decades.

In Lee’s picture, “Jack Whinery, Homesteader

and Family, Pietown, New Mexico, September, 1940,” (see it top of this review) a handsome young working-class man and his

blonde, blue-eyed wife, holding their toddler son, stare resolutely into the

camera. Behind them is the

cardboard-covered wall of their new rough-built shack with plastic stretched

over an unframed window. A swatch of flowered fabric for curtains is

tentatively pinned up near the window. A Coca-cola poster is hanging on the

wall.

To me this picture says, “We are a God-fearing, can-do American family, and we are not afraid.” My question might be, Why not? The Great Depression is still hanging on, and another great war is looming in Europe. Yet, as

a viewer, I believe in this family. Here in America they’ll make it, I'm sure.

In the final reel, I tell ourselves, everything will work out.

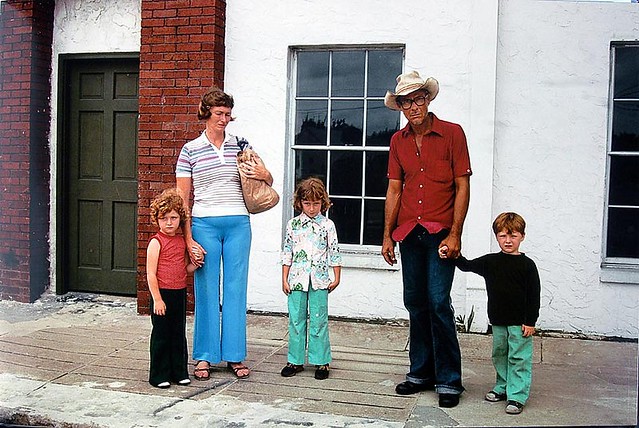

Mitch Epstein, Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983

Mitch Epstein, Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983

Mitch Epstein, Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983

Mitch Epstein, Ybor City, Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), 1983

By 1983, when Mitch Epstein made “Ybor City,

Florida (Mother with Brown Paper Bag), ” belief is harder to come by. In Epstein’s

picture a thin man in a ragged straw hat glares belligerently at the camera.

Behind him, dressed in cheap, ill-fitting clothes and clutching an old paper

bag, his wife and three young children stand apart, round-shouldered, looking down at the

sidewalk or off to the side, anywhere but at the camera. They are waiting for the

shame to end. But it won’t.

What has changed?

Flash forward to 1997. Joel Sternfeld ‘s “A Man

Walking Home, Washington Market Park, NYC” shows a well-dressed

late-middle-aged black man standing by a lamppost in a lush city park in an

upscale neighborhood. The man leans back, smiling, balancing two shopping bags.

We see that he is next to a garden. Tomatoes are growing. A sunflower nods its

golden head. The man’s mood seems peaceful, friendly. After so many years, he looks like he feels

at home.

What has changed?

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

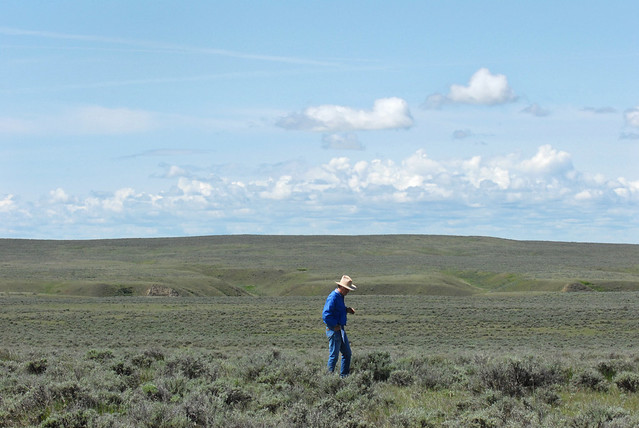

Big Sky

Monday, March 11, 2013

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

Other Landscapes Under the Sun

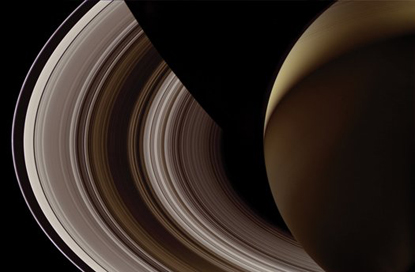

Michael Benson’s “Planetfall” at Hasted-Kraeutler Reviewed by Tim Connor

Human

imagination has been soaring into the heavens for millions of years, but it

wasn’t until 1961 that Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin actually left Earth’s

atmosphere. Between 1969 and 1972

twelve Americans walked on the moon, but that’s as far as human bodies ever got.

Increasingly, in recent years, space travel has meant virtual ride-alongs on remotely-piloted

robotic spacecraft with engineered senses. It is from these otherworldly robots

that writer-photographer Michael Benson mined visual data for his powerful exhibit,

“Planetfall,” at Hasted-Kraeutler.

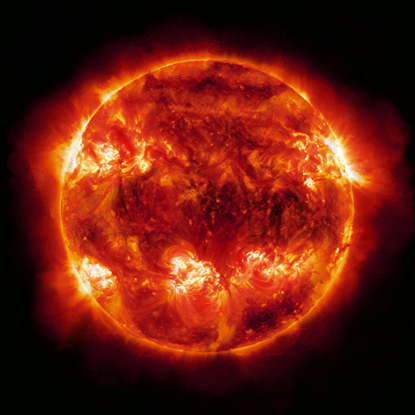

It’s no surprise that “Planetfall’s” images are technically extraordinary. Some of the pictures of Mars, for instance, were made with NASA’s HIRISE camera, which has a 19.7-inch aperture, allowing it to render images of one foot per pixel. Such cameras create images that astonish, not only because they really exist but also because they seem impossible (or faked). The show’s images of Saturn’s rings, for example, have a rigid, abstract geometric precision that makes them appear to be machines. On the other hand, Io, Jupiter’s highly volcanic fifth moon, looks like a hunk of pocked and mouldy yellow cheese.

Benson explains this approach with a quote from theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg: “We have to remember that what we see is not nature herself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” In “Eclipse of the Sun by the Earth,” for instance, an orangey-red hemisphere of sun emerges from Earth’s shadow literally boiling --in fact, half-exploding -- with heat. From the writhing gases on the sun’s surface, hellish flowers seem to be blooming, their centers blazing with incandescent yellows. A viewer is hard-pressed not to back away from this ferocious image. And this is not just a reaction to its imagined heat. This sun appears to be in a violent rage. We can feel its uncontrolled wrath. There is danger in this wrath – and beauty too. We can glimpse why ancient people gave such strong personalities to their god-planets and stars.

It’s

interesting that Benson finds very different metaphors in his pictures of Earth’s

nearest sibling, Mars. The

planet’s red rock and sand deserts , barren valleys and far-off low ranges of hills

are not so different from views found on our own planet. Thus Benson’s “Sunset

on Mars” is weirdly familiar, even with its tiny, distant sun and

magenta-tinted atmosphere.

Why,

I wondered, is this Martian sunset so much more melancholy than any I’ve seen

on Earth? Perhaps it’s because this

and the other Martian photographs in the show seem to bear out a mood detectable

in our long-standing, obsessive fantasies about vanished civilizations on the

Red Planet. The NASA photographs

are detailed; they show no canals. Yet the Mars in these pictures seems spent, desolated;

its time over; its ripeness gone. Something must have happened ...

"Sun on the Pacific," Michael Benson, All rights reserved

Here

I’m in mythical territory, of course. But perhaps I’m not being whimsical.

Could the cautionary feel of the Mars pictures reveal an aspect of Benson’s

curatorial intentions? Here’s a piece of evidence. My favorite picture in

“Planetfall,” titled “Sun on the Pacific,” shows a softly curving Earth horizon

pushed up against an inky black crescent of space. When I first gazed at this

picture’s large-scale print on the wall, I felt oddly weightless, a speck

floating dreamlike above blue and pink clouds that framed a golden gleam of sunlight

on a peaceful ocean. And then I

realized my point of view – the point of view Benson had chosen for me -- was a

spaceship cruising the last leg of its homeward journey. And the Earth had

never looked more beautiful.

More

evidence. In a recent interview Michael Benson said the following: “I’ve looked

at thousands of images [of Earth] from space over the last few months, and many

images show evidence of planetary distress. For instance you can see smoke

filling the air of the entire continent of South America due to the burn off of

jungles. My view is that an honest look at the early twenty-first century solar

system needs to include visual evidence of climate change here on the third

planet. “

Also published in New York Photo Review, 03/2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)